FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

decoding egyptian

decoding egyptian

WHAT DOES LANGUAGE MEAN? NICHOLAS SKETCHES

THE HISTORY OF DECIPHERING EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPHICS.

read the essay now >>

WHAT DOES LANGUAGE MEAN? NICHOLAS SKETCHES

THE HISTORY OF DECIPHERING EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPHICS.

read the essay now >>

|

The decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphic writing in the early nineteenth century is in many ways a type case for decipherment in general. Not coincidentally, scholarly thought about Egyptian writing in the period after it fell into disuse, and before it was deciphered, offers an object lesson in how not to think about writing. 1 Since its development, perhaps as early as 3400 B.C., Egyptians used the hieroglyphic system primarily for royal and religious texts. Cursive scripts—hieratic and demotic—were used in other contexts, especially to write on papyrus . The hieroglyphic system persisted in Egypt despite a series of conquests by foreign empires with different scripts: the Persian Empire (Persian), Alexander the Great and his Ptolemaic successors (Greek), and lastly Rome (Latin). The script finally died out by the end of the fourth century A.D., after non-Christian temples were closed throughout the Roman Empire, and knowledge of the hieroglyphs no longer conferred cultural capital. But by the first century B.C., the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus was already reporting to a Greek-speaking audience that hieroglyphic writing “does not work by putting syllables together … but by drawing objects whose metaphorical meaning is impressed on the memory.” |

Writing in the second century A.D., the neo-Platonic philosopher Plotinus likewise argued that Egyptian writing corresponds to a vision of meaning and truth having nothing to do with language or dialogue. Instead of using characters to represent sounds, sounds to compose words, and arrangements of words to present propositions, the “wise men of Egypt … drew … a separate sign for each idea, so as to express its whole meaning at once. Each separate sign is in itself a piece of knowledge, a piece of wisdom, a piece of reality, immediately present. There is no process of reasoning involved, no laborious elucidation.” This ideographic theory—that symbols stand for complete thoughts lacking a relation to spoken language—was rediscovered in the Renaissance and remained for centuries not only the standard scholarly interpretation of Egyptian writing, but a model for what a truly “philosophical” writing system would be like: monologic, authoritarian, mediated by iconicity and metaphor, but never by speech. It was also completely wrong. On July 1, 1798, a French fleet headed by a young general named Napoleon Bonaparte landed at the Egyptian port of Alexandria, intending to “liberate” Egypt from nominal control by the |

|

Ottoman Empire and install a French-dominated client government. In keeping with Enlightenment principles, the expedition included a contingent of scholars and engineers, whose purpose was to modernize the country’s agriculture and infrastructure, and to collect Egyptian antiquities. Three years after the invasion began, British and Ottoman armies forced the French to withdraw, and most of the artifacts the scientific expedition had collected passed to British control. Among the artifacts discovered by the French was a massive fragment of a granodiorite stele that French troops had found in the foundations of a fort in the town of Rashid, which they called Rosetta . The Ottomans had built the fort, but the stele—the Rosetta Stone—was much older. |

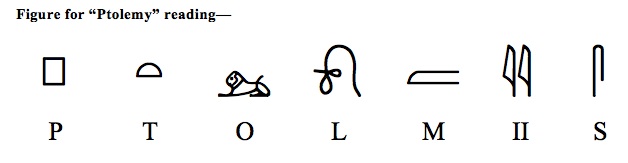

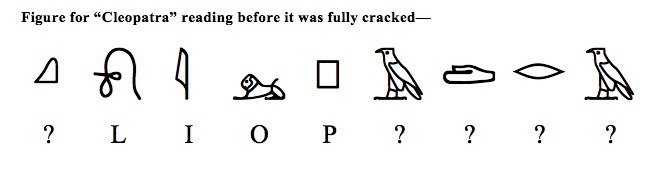

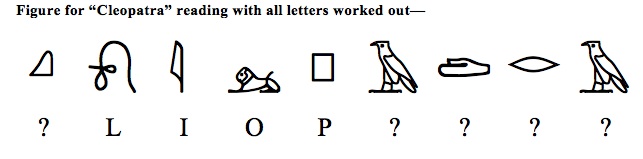

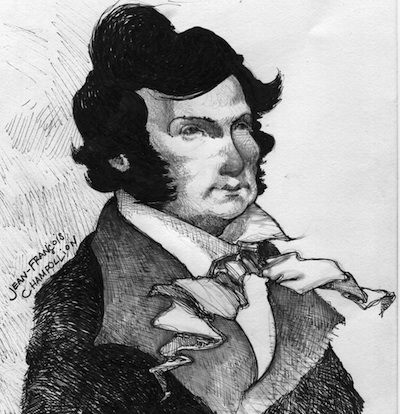

It bore three inscriptions: a badly damaged one in Egyptian hieroglyphs, a better-preserved inscription in demotic (the cursive, vernacular Egyptian script), and one in Greek. The Greek text proclaims the establishment of a religious cult in honor of Ptolemy V, the king of Egypt and the heir to the Ptolemaic dynasty established after the Macedonian conquest. Helpfully, it also states that the hieroglyphic and demotic texts (“sacred writing 'and' document writing”) bear the same message. 2 Although the Rosetta Stone inscription was almost immediately published, it was more than twenty years before anyone conclusively demonstrated a correspondence between words in the Greek and hieroglyphic texts. The scholar who did it, Jean-François Champollion , was a polyglot whose interest lay in what were then called “oriental languages”—mainly members of the Afroasiatic language family, including Arabic, Hebrew, Syriac, and especially Coptic, a late form of the Egyptian language written in a modified Greek alphabet. In 1822, following up on a suggestion from his mentor, Silvestre de Sacy , he proposed that a group of seven hieroglyphs enclosed by an oval cartouche read p-t-o-l-m-ii-s, for Ptolemaios, Ptolemy. He applied the proposed sign values to two other groups of hieroglyphs enclosed by his Sure enough, the proposed ptolmiis spelling |

|

cartouches, this time on an inscribed obelisk believed to have been dedicated by Ptolemy and wife Cleopatra. Sure enough, the proposed ptolmiis spelling appeared again. Applying the same sign values to the other cartouche produced ?-l-i-o-p-?-?-?-?, where the the sixth and ninth signs were the same. The implication was that the first sign had to be k, the seventh sign a different character t, the eighth r, and the identical sixth and ninth signs a , for Klêopatra. Champollion went on to check these proposals against other names recorded in other inscriptions—other members of the Ptolemaic dynasty and various Roman emperors—each time confirming his readings and adding new phonetic characters to the list. At this point, Champollion had shown how Egyptian scribes dealt with names. It remained to be determined how the rest of the script worked, and at first Champollion assumed that the ideographic model was correct. Before long, though, he realized that the same characters that were used to spell personal names were also by far the most common signs in the script—not just in Roman times, but throughout its whole history. Treated phonetically, they yielded sensible, grammatical readings in a language recognizable as ancestral to Coptic. |

At the same time other determinative signs appeared to categorize the people named in inscriptions as being “men,” “women,” “deceased,” and so on. Still, others seemed to be logograms, signs that stood for whole words and could substitute for phonetic spellings, but that were integrated into the grammatical structures of the texts. Although he never explicitly distinguished between these last two categories of signs, calling both of them “ideograms,” Champollion had demonstrated that true ideography—using signs to stand for ideas—played only a supporting role in the Egyptian system. Even at that, these ideograms, called determinatives, only help readers select the correct phonetic readings of other characters. They do not serve as the primary vehicles of information themselves. In exploding the ideographic model of Egyptian writing Champollion showed that even esoteric, hieroglyphic scripts do not “directly” record thought. Instead, thought is mediated by language. Egyptian scribes weren’t just recording ideas on their monuments and scrolls: they were recording them in Egyptian.  See next page for bio and references... |

|

Nicholas Carter was born in Houston, Texas. He received his BA in philosophy from Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio. He the attended the University of Texas in Austin where he earned an MA in Latin American Studies, specializing in the study of the Mayan civilization. There he studied with Dr. David Stuart. Currently, he is a PhD candidate in archaeology at Brown University, where he studies under Dr. Stephen Houston. *** 1. Maurice Pope, The Story of Decipherment: From Egypitian Hieroglyphs to Maya Script. Revised edition. Thames and Hudson, New York, 1999. 2. R. S. Simpson, “The Rosetta Stone: Translation of the Demotic Text.” The British Museum. www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/article_inde/r/the_rosetta_stone_translation.aspx For more fun figures see the appendix on the following pages. |

|

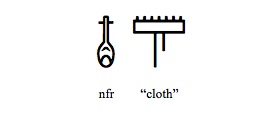

All the Egyptian inscriptions have been rearranged to read from left to right in one straight line, for readers’ convenience. |

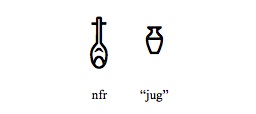

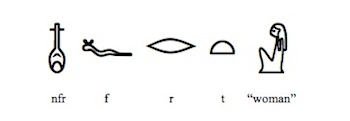

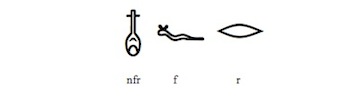

Jean Capart, 1968, Je lis les hiéroglyphes. Presses Universitaires de Bruxelles, Brussels. (1) This sign represents the consonantal root nfr. In Egyptian, as in some modern, related languages like Arabic and Hebrew, words that share a consonantal root are conceptually related to each other. Words having to do with that concept are formed by adding vowels, prefixes, and suffixes to the root. For example, in Arabic, the consonantal root ktb has to do with “writing.” Kātib means “writer,” while kitab is the word for “book.” In Egyptian, nfr is a root for words connected to “beauty” or “goodness.”  |

(2) Scribes could use signs for single consonants to clarify the readings of consonantal roots. Here, the first character is nfr. The second character is the letter f, and the third is the letter r. An Egyptian reader would have read the whole sequence as nfr, not nfrfr—the second and third characters are only there to “reinforce” the sound of the first character. (3) Modern Semitic and Afro-Asiatic writing systems like Hebrew and Arabic sometimes use supplementary marks (“vowel points”) to record vowels. That way, readers can tell which of several possible pronunciations of a consonantal root is the right one. Egyptian scribes took a different approach. (4) This spelling corresponds to the word for “clothing.” The first character is nfr. The second is a determinative for “cloth.” Together, they tell us that the correct reading here is a word that (1) includes the consonantal sequence n, f, r, and (2) refers to something made out of cloth. |

|

(5) This spelling gives us the word for “wine” or “beer.” Just like “clothing,” this word uses the consonantal root nfr. Since Egyptian doesn’t normally record vowels, there would be no way to tell whether the scribe meant “clothing” or “beer” if he had just written the consonantal root. The second sign, depicting a jug, resolves the ambiguity by telling us that the right word means a kind of liquid.

|