FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

reading texts

reading texts

DECIPHERING ANCIENT TEXTS GERMINATED

IN MODERN THOUGHT. NICHOLAS OUTLINES EPIGRAPHY.

read the essay now >>

DECIPHERING ANCIENT TEXTS GERMINATED

IN MODERN THOUGHT. NICHOLAS OUTLINES EPIGRAPHY.

read the essay now >>

|

As central as it is to scientific archaeology, stratigraphy doesn’t receive much attention in its popular presentations. Instead of digging and drawing, movies tend to show archaeologists deciphering ancient, plot-related texts, whenever they’re not fighting Nazis or extraterrestrials. Think of Harrison Ford spot-translating an Inca inscription by “running it through the Maya” in the fourth Indiana Jones installment. Or how, in Aliens vs. Predator, a panel containing a mixture of Aztec, Egyptian, and Cambodian hieroglyphs recounts a gruesome version of the “aliens started human civilization” trope that’s been kicking around since the 1960s. Actual decipherment is not as straightforward as such films make it out to be. The excitement of epigraphy—the study of ancient inscriptions—is more like that of detective work. Writing systems are like ciphers that have to be broken. Once they are, scholars start to have access to the meanings that inscriptions encode, both consciously intended by their producers and otherwise. Epigraphy thus overlaps with fields including art history, archaeology, and philology, but its overriding concern is with linguistic signs. |

Much of modern linguistics and linguistic anthropology derives from the work of two scholars active in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure and American pragmatist philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce. Saussure distinguished between actual instances of speech, parole, and the sets of rules—vocabularies and grammars—that make up a language, langue, as a system. A langue, for Saussure, is made up of reciprocal relationships among what he calls “linguistic signs.” A linguistic sign, in turn, is a relationship between a “signifier” (signifiant, a pattern of sounds) and a “signified” (signifié, a mental concept). Words are one kind of linguistic sign, although we could also think of things like prefixes and suffixes in the same terms.

|

|

In Saussure’s model the connection between signifier and signified is arbitrary. To take an example from English, there is no inherent necessity for the sound pattern of the word "tree" to mean what it does. All that is necessary is that the sound pattern be distinguished from other such patterns, like "tray" or "three"; that the concept of a tree be distinguished from other concepts; and that the relationship between the two be established by social convention. Likewise, the connection between a linguistic sign as a whole and its “referent”— a specific instance or thing to which it could be applied, is also conventional. An actual tree is not the same thing as the concept of “tree,” and in fact we could conceptualize things differently—we might use only one word for all kinds of plants, or we might assign each species of tree its own word, without having a name for all of them together. Saussure’s semiology emphasizes such structured oppositions in ideal systems, making it a natural working model for scholars trying to decipher ancient writing systems. Charles Sanders Peirce was a polymath whose interests lay more in mathematics, logic, the physical sciences, and the philosophy of science, |

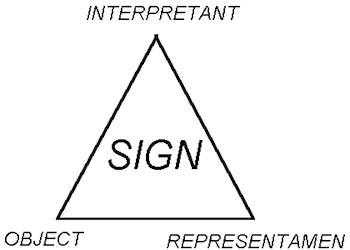

than in written or spoken language. Nevertheless, many linguistic anthropologists have found his theory of meaning in cognition useful, because it accounts for other kinds of meanings than an arbitrary relationship between signifier and signified. Unhappily for aspiring semioticians, Peirce uses some of the same terms as Saussure, but in a different sense. Instead of being a two-part model made up of a signifier and a signified concept, the Peircean equivalent to Saussure’s sign is a “sign relation” among three components. The first component is what Peirce calls the “representamen,” or, confusingly, the “sign." A representamen is anything from a logical proposition to a cloud of smoke on the horizon that “stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity.” 2 In contrast to Saussure’s model, the Peircean sign relation also includes the “object” for which the representamen stands. For Peirce, an object is “anything we can think, i.e. anything we can talk about." 3 He sees a causal relationship between sign and object: an object “determines a sign 'so' that the latter determines an idea in a person’s mind.” That idea, impression, or effect--the third element of the sign relation--is called the “interpretant.” 4 This is the |

meaning that the cloud of smoke on the horizon is transmitting, that which is interpreted. One important feature of Peirce’s model is that meaning does not exist atemporally in an abstract system like the Saussurean langue. Instead, meaning happens in particular cognitive events such as instances of mediation between object and interpretant. In other words, a sign is not a sign at all unless, and until, it is interpreted. Such interpretations always happen upon some basis, or ground, which Peirce defines as the relationship between the object and the representamen. |

A sign whose ground is that it resembles its object in some way is an “icon.” Second, something that is understood as a sign because of its causal, spatial, and/or temporal contiguity or contact with its object is an “index.” As such, both grounds, iconicity and indexicality, have to do with facts about the world that remain true regardless of whether meaning is actually being produced. As an example, take a forest fire. A forest fire would still produce smoke, and a painting of that fire would still resemble the actual fire, even if there were no observers around to interpret the smoke as an index, or the picture as an icon. By contrast, with the third kind of Peircean ground,“symbolism," a sign is connected to its object by convention alone. 5 Symbols, then, closely resemble Saussure’s arbitrary linguistic signs, but they can be far more complex. Words, national flags, propositional statements, and logical syllogisms can be mountains and buildings. 6 Following Peirce, if meaning does not wholly exist in signs themselves, but instead has to be produced in acts of semeiosis conditioned by context and habit, then accessing the meanings of ancient symbols has (at least) two dimensions. One way of proceeding is to attempt to understand the symbols’ “situations,” or their relation to their producers, intended readers, and physical settings. |

|

For immovable symbols like a petroglyph some aspects of setting are obvious, but the cultural geography of their original contexts may be lost forever. Another approach is to try to “extract” symbols’ meanings. That is, to reproduce some of the meanings that competent readers would have produced in those situations. 7 This approach also has its limits. For the overwhelming majority of features in the archaeological record that meant something symbolically to someone at some time—whether natural features like rock formations or cultural artifacts like pots or cave paintings— the symbolic meanings can never be recreated. Decipherment tries to explain the actual arrangements of signs in inscriptions—a written parole—by reference to the rules of a langue in which the inscription is written. In some cases, scholars can make educated inferences about intended meanings based on factors like the internal structures of visual compositions or the spatial, temporal, and social distribution of artifact types. One particular kind of artifact, however, offers the possibility of detailed, testable reconstructions of many of their meanings. |

Those artifacts are written texts, and the kind of extraction proper to them is decipherment. Decipherment aims at understanding the connection between a script and a spoken language. For that reason, its natural intellectual framework is more structuralist than Peircean. Decipherment tries to explain the actual arrangements of signs in inscriptions— a written parole—by reference to the rules of a langue, in which the inscription is written. At the same time, it tries to tie that written langue to an imagined (“reconstructed,” as epigraphers like to say), spoken langue, and to assign that spoken langue a spot in the family tree of human languages. Of course, epigraphers can and do investigate other kinds of meanings in texts, like how choices about style or dialect might have helped construct past social identities. Many of those kinds of questions are best approached from a semiotic perspective, but they are distinct from decipherment as such. A successful decipherment meets three standards. First, a deciphered script is transcribable: individual characters in a text must be identifiable as instances of distinct signs in the abstract, written langue, whether or not their phonetic or semantic values are known. |

|

For example, an epigrapher working thousands of years in the future, perhaps after the collapse and rebirth of literate civilization, would satisfy this requirement if she worked out from their visual forms and contextual clues that g , g, g, and g are all instances of a single sign g in the Latin alphabet, even if she didn’t yet know how it was pronounced. Undeciphered signs might be assigned letters or numbers to identify them in transcriptions. Second, an inscription in a deciphered writing system can be transliterated.This means that a given arrangement of signs is known to cue one, or more, small number of possible phonetic utterances. Those utterances should be grammatical and intelligible in a reconstructed langue, that should ideally emerge from previous historical linguistic findings checked against the actual content of inscriptions. For example, Maya hieroglyphic spellings make sense in the light of independent, historical reconstructions of ancient Mayan languages, at the same time that they offer information about those languages’ evolution. Finally, the utterances corresponding to deciphered inscriptions can be translated into living languages, and vice versa. A language is not considered |

deciphered until each of these criteria is met. In 1995, renowned archaeologist Michael Coe noted five characteristics that the decipherments of numerous ancient scripts since the nineteenth century all had in common. First, successful decipherers had access to a substantial number of texts. Second, there was enough historical linguistic evidence to suggest the languages the script encoded, and many inscriptions were long enough to include tell-tale grammatical features. Third, the cultural contexts in which those texts were produced were reasonably well understood. Fourth, for scripts with a large number of logograms (signs standing for whole words), pictorial imagery accompanying some inscriptions provided additional context. Finally, and perhaps most crucially, scholars had at least one bilingual inscription in which the undeciphered script and a known writing system appeared to record the same information. For two visually complex scripts, Egyptian and Maya hieroglyphic writing, all these criteria were met in one way or another and successful decipherments resulted. For another script, Linear A, a crucial piece of the puzzle is still missing.

For bio and notes see following page...

|

|

Nicholas Carter was born in Houston, Texas. He received his BA in philosophy from Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio. He the attended the University of Texas in Austin where he earned an MA in Latin American Studies, specializing in the study of the Mayan civilization. There he studied with Dr. David Stuart. Currently, he is a PhD candidate in archaeology at Brown University, where he studies under Dr. Stephen Houston. |

1. Ferdinand de Saussure, 1959 (1915), Course in General Linguistics. Edited by Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye. Translated with an introduction and notes by Wade Baskin. McGraw-Hill, New York. 2.Charles S. Peirce, Collected Papers 2.228. Edited by Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. 3. Charles S. Peirce, “Reflections on Real and Unreal Objects,” MS 996. 4.Charles S. Peirce, Collected Papers 8.343. Edited by Arthur W. Banks. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. 5. Charles S. Peirce, M.S. 599: 43. 6. Charles S. Peirce, Collected Papers 2.261-2.263. Edited by Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. 7. Stephen D. Houston, 2004, “The archaeology of communication technologies.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 33, pp. 223-250. 8.Michael Coe, “On Not Breaking the Indus Code.” Antiquity, vol. 69, pp. 393-395. |