FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

father strata

father strata

THE STRATA REVEAL TIME FORMING. ARCHAEOLOGIST NICHOLAS UNVEILS THE LAYERS OF STENO'S STRATIGRAPHY.

read the essay now >>

THE STRATA REVEAL TIME FORMING. ARCHAEOLOGIST NICHOLAS UNVEILS THE LAYERS OF STENO'S STRATIGRAPHY.

read the essay now >>

|

In 1988, Pope John Paul II beatified Niels Stensen, a seventeenth-century scientist and Catholic bishop from Denmark, better known—well, perhaps not that much better—as Nicholas Steno, the father of stratigraphic analysis. When, as seems likely, he is eventually canonized, stratigraphy may get its own patron saint. Strictly speaking, stratigraphy is the study of layering, or stratification, in geological and archaeological contexts: how strata are laid down, modified, and eroded over time. It is also a handy metaphor for anyone, like archaeologists, who think a lot about the past. Seen through this lens, the present moment is a surface layered on top of past events, accumulations of meanings and memories across generations of people. But those events are subject to modification or erosion through accidental or intentional forgetting. Occasionally, someone uncovers a forgotten stratum of history, which takes its place in the stratigraphic sequence of reality, a reality reinterpreted with each discovery. Historical strata build up at the scale of the whole human species and have an analogue in the individual human life. Who I am now is an accumulation of people I was in the past, and what I do as an archaeologist-in-training is built on a deep sequence of intellectual and practical strata—all subject in the course of time to |

reinterpretation, rediscovery, obliteration. My strata begin in 1981 in Houston, Texas. Layer 1: I grew up just outside the city limits in a suburban landscape that had been forest and farmland not long before. Like a lot of children, I took an early interest in dinosaurs, and had a pretty substantial collection of plastic ones. Encouraged by my parents, who made sure that my sisters and I had abundant access to books and museums, I read and pretended my way from dinosaurs through Ice Age mammals and cavemen to ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. Layer 2: Somehow or other I got stuck on ancient civilizations, especially ones with interesting and exotic art and writing systems, and before long I found that no graphic systems fit the bill better than those of pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica. I was sure, as a young boy, that I would be an archaeologist when I grew up, but I took my B.A. in philosophy, possibly on the theory that that would be a more practical choice of career. All the same, it seems in retrospect that I was aiming, unconsciously, at Mesoamerican archaeology. Layer 3: At college—Our Lady of the Lake University, in San Antonio, Texas—I gravitated towards courses on intellectual history, |

|

anthropology, and ancient and Colonial-era Mesoamerican culture. Layer 4: Unsure of what to do with myself and my newfound degree, I moved to Austin after graduation and (stereotypically enough) found temporary work as a barista. One of my housemates, Katharine Lukach, happened to share my interest in Mesoamerican archaeology and art history: in fact, she was at that time finishing her own B.A. in anthropology at the University of Texas. Through her intercession, I was able to audit an introductory graduate course in Maya hieroglyphs with David Stuart, a pioneer of Maya epigraphy who had just started teaching at U.T. Layer 5: It was soon very clear that I’d found my calling, even if it wasn’t as practical as philosophy. I moved on to the advanced course, entered the university’s M.A. program in Latin American Studies on Prof. Stuart’s recommendation, and wrote my master’s thesis on the Zapotec writing system of ancient Oaxaca. Layer 6: I’d also found my one right partner in life, and Katharine and I got married in 2007. In 2008, again thanks to professorial support, I started in the Ph.D. program at Brown University, where I’ve been studying until the present day under Stephen Houston, another luminary in Maya epigraphy and archaeology. I now work on an archaeological |

project at the Classic Maya site of El Zotz, in present-day Petén, Guatemala, which Prof. Houston directed until the close of the project’s first phase earlier this year. Thousands of years of human history have passed in that place and laid down their strata of places, names, and people.

II The intellectual strata that I work with also have a varied history, involving layers of people, ideas and time. And stratigraphy itself has layers of development that begin with the Danish bishop, Nicholas Steno. He was one of those restless intellects, so characteristic of seventeenth-century European science. He contributed to fields ranging from anatomy to theology. Raised Lutheran, he moved to Italy in 1666, at 28 years of age. There, he wrote his most important scientific works. In one of those works, De solido intra solidum naturaliter contento dissertationis prodromus, published in 1679, Steno set out to explain how solid objects like fossils, crystals, and metal or mineral veins could have naturally ended up inside masses of rock.Of special interest were the triangular glossopetrae, “tongue stones,” that were then being dug up in Malta. The scholar Fabio Colonna had proposed in 1616 that tongue stones were actually sharks’ teeth—as in fact they were—but the general consensus was that they grew naturally in the |

|

rocks where they were found. (Pliny the Elder, in his Naturalis historia, had long ago skeptically noted the popular opinion that they instead fell from the sky during the waning of the moon.) Steno observed that objects like tree roots that grow slowly in or among rocks gradually fractured the rocks and deformed themselves, but that tongue stones all closely resembled one another, being undistorted by slow growth in a confined space. He revived Colonna’s hypothesis, combining it with the then-novel corpuscular theory of matter to suggest how teeth could have been replaced by stone one particle at a time without changing their shapes. Showing that tongue stones were shark's teeth still left the question of how they had gotten into the chalk cliffs of Malta in the first place. But showing that tongue stones were sharks’ teeth still left the question of how they had gotten into the chalk cliffs of Malta in the first place. To explain that, Steno had to propose three general rules that, as it turned out, lay the foundations for all subsequent, scientific stratigraphy.If the rock strata were formed as particles fell out of suspension in seawater, Steno reasoned, they must have originally been deposited more or less |

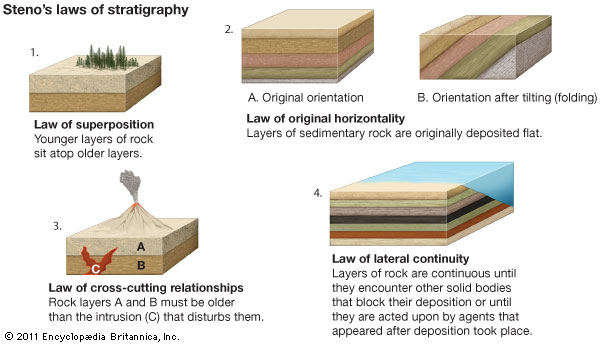

horizontally (the principle of original horizontality). The lower layers in a stratigraphic section must be older than higher ones, as long as nothing has happened to disturb the orientation of the strata (the principle of superposition). Finally, strata laid down in this way would have extended laterally and continuously in all directions, limited only by the amount of sediment being deposited and the area and shape of the sedimentary basin. This principle of lateral continuity means that any exposed edges in a sedimentary stratum are the result of erosion or dislocation, and that two compositionally identical strata cross-cut by a discontinuity—a void or an intrusion—were probably once a single deposit. (See the annotation below.) As a small-scale example, think of a shallow, rain-fed pond that formed in a valley, in a natural depression in the bedrock. Seasonal rains wash in particles of soil that settle to the bottom of the pond, forming very thin layers of silt year after year. At some point a nearby volcano erupts, blanketing the valley with ash that likewise ends up at the bottom of the pond. Small amounts of silt continue to accumulate on top of the ash layer, sealing it off. Now imagine that some human beings arrive and clear the valley slopes for agriculture and firewood. With the ground cover |

|

the soil on the hillsides starts to erode during the the rainy seasons faster than it can be restored, and dirt and clay wash down the slopes to fill up the pond. Later, one of the original farmers’ descendants dies, and his relatives dig a hole down to bedrock and bury him there, filling in the grave with a mix of all the soils they had dug up. Soon afterwards, the volcano erupts a second time and deposits a second layer of ash on top of the grave. Fed up with life in such an unstable environment, the farmers leave and the forest grows back, producing a new layer of living topsoil. If we were to dig a trench across the former pond, the strata we revealed would tell its story. For the most part, the spatial order of the strata, from the deepest layers to the surface, would correspond to the order of events (superposition). Since those layers mostly lie flat, we could infer that the particles comprising them fell out of suspension in water (original horizontality). The discontinuity between the earth in the farmer’s grave and the layers on either side of it would tell us that the farmer died after the volcano erupted and the pond silted up, even though his body is lower than the layers of ash and eroded soil. A fourth rule of stratigraphy, the the principle of faunal succession, was proposed in the early nineteenth century by the English geologist William |

Smith, who noticed that the same pattern of superimposed strata appeared again and again in canals and mining pits across southern England, and that each layer contained some fossils that were unique to itself 1. As refined by Sir Charles Lyell in the 1830s, the principle of faunal succession states that strata widely separated in space can be identified and dated based on the fossils they contain. For example, if two rock strata from different parts of the world contain fossils of a single species of trilobite known to have existed for only a few hundred thousand years, we can infer that both strata had to have been deposited during that period. Together with Steno’s first three stratigraphic principles, the fourth rule came to revolutionize human beings’ ideas about the world and our place in it. The founding ideas of geological stratigraphy are some of the strata underlying both Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and later models of continental drift. III The transition from geology to archeology makes up another layer of intellectual stratum. Archaeology deals with much shorter periods of time than geology does, and frequently with much smaller areas of space. Moreover, it looks in the stratigraphic record for evidence of human agency, |

|

which is not always as predictable as natural processes. Geological stratigraphy therefore had to be adapted for archaeological use. Prehistoric people had continued to make some things out of stone and bronze even after the introduction of new technologies. A Danish antiquarian named Christian Jürgensen Thomsen 2 independently worked out the archaeological equivalent to the principle of faunal succession, using artifacts instead of fossils. Working for the newly established Royal Commission for the Preservation and Collection of Antiquities, Thomsen was faced with the problem of chronologically organizing a vast collection of prehistoric artifacts from all over Denmark. Thomsen was aware that there had been a time when tools and weapons had been made of bronze, not iron, and he suspected that stone tools had been used before that. But prehistoric people had continued to make some things out of stone and bronze even after the introduction of new technologies, and the collection included plenty of artifacts made from glass and metals other than iron and bronze.Thomsen’s solution was to determine the kinds of artifacts that did or did not co-occur in sealed archaeological contexts like tombs or hoards. |

From the relative proportions of different materials, styles, and artifact types in those sealed deposits, Thomsen identified five successive cultural phases: an Old and New Stone Age, a Bronze Age, and an Early and Late Iron Age. When similar artifact assemblages were found in unsealed contexts, those deposits could then be placed in the general chronological sequence. Later excavations in the Near East of many-layered tells—elevated settlements built up over thousands of years of habitation, destruction, and reconstruction—vividly demonstrated the utility of combining stratigraphic excavation with artifact studies. Strata laid down by human beings, of course, tend to look very different from natural ones. Our deposits tend to have much smaller footprints: walls, firepits, the foundations of houses. We dig holes in the earth and build complex architecture. Because of this complexity, archaeologists Edward Harris and Richard Reece 3 found it necessary to modify the principle of superposition with a fifth rule, the principle of stratigraphic succession. This axiom states that a stratigraphic sequence is a physical record of the sequence in which a site was modified over time, and that any stratigraphic unit takes its place in the stratigraphic sequence of a site from its position between the latest previous |

|

deposit and the earliest subsequent deposit with which it is physically in contact. In our example of the silted-up pond, the farmer’s grave is physically in contact with all the other strata except the topsoil. The latest previous deposit (the eroded dirt and clay from the hillsides) and the earliest subsequent deposit (the ash from the second volcanic eruption) tell us when the grave was dug and filled in relation to the other deposition events. Since the grave is later than the eroded soil, and the eroded soil is later than the first eruption, the grave must be later than the first eruption. (See the annotation below.) Strata are three-dimensional objects, but the salient information about them has to be communicated in two dimensions in articles and field reports. One means of presentation is the stratigraphic section, a more or less stylized drawing of one wall of an excavation unit showing the different strata as they appear to the eye. The other is the Harris matrix, named for and developed by the same Edward Harris, in which stratigraphic relations are shown abstractly as lines connecting boxes that represent deposits 4. Archaeological best practice is to produce a Harris matrix during excavation, since doing so forces the excavator to interpret the relative chronology of strata on the spot. |

Stratigraphy is perhaps as close as archaeological evidence ever gets to a language-like syntax. Just as the meaning of a sentence emerges not just from the words in it, but from their order relative to one another, the story of a site can emerge from careful attention to stratigraphic detail. (See the annotation below.) When archaeologists combine enough of those site-specific stories, we start to produce larger (and, we hope, ever more accurate) regional histories. From these, we can suggest anthropological theories about human culture and behavior in general.  Nicholas Carter was born in Houston, Texas. He received his BA in philosophy from Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio. He attended the University of Texas in Austin where he earned an MA in Latin American Studies, specializing in the study of the Mayan civilization. There he studied with Dr. David Stuart. Currently, he is a PhD candidate in Archaeology at Brown University, where he studies under Dr. Stephen Houston. See the next page for references. |

|

1. William Smith, 1816, Strata Identified by Organized Fossils. London. 2. Bruce Trigger, 2007, A History of Archaeological Thought, Second Edition, pp. 121-129. Cambridge University Press, New York. 3. Edward Harris and Richard Reece, “An Aid for the Study of Artifacts from Stratified Sites.” Archaeologie en Bretagne, vol. 20-21, pp. 27-34. 4. Edward Harris, 1989, Principles of Archaeological Stratigraphy, Second Edition. Academic Press, New York. |