FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

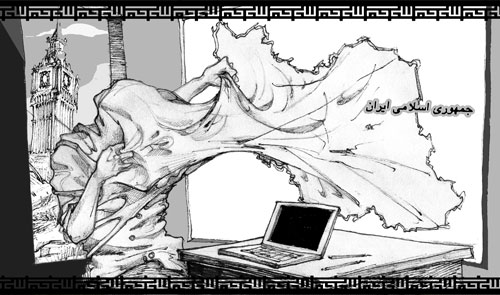

IRAN'S GREEN WAVE SUBSIDES IN EERIE SILENCE.

'ANONYMOUS' REVEALS A SECRET FAMILY HISTORY OF CHAINS.

read the essay now >>

|

I Six years ago, I spent three months in Tehran learning to read and write Farsi at The Dehkhoda Language Institute. Every morning, on my walk to school, I passed pedestrians fiddling with their hijabs, patrolling morality police, and a "Death to America" mural that was painted on the side of a tower block near my apartment.My classroom in Dehkhoda was stale. It was a tall, grey and largely empty hall. The notable things in the room were the desks and chairs, the blackboard and the two adorning photos of Khomeini and Khamenei that hung above it. I started classes in the beginner’s set. Farsi is my mother tongue, but I went to school in England, so I had never learnt the Iranian alphabet. No one else in my class spoke Farsi so everything went agonisingly slowly. After a few days, I was ready to move up a level. Mina, my attractive teacher who I was reluctant to leave, sensed this. One day, after class, she called the Institute director to facilitate a switch. Surprisingly, for such a sexist society, the director was also female. |

The director and I had a short exchange. I remember it well.

“Hello,” she said to me in Farsi. “Well, I am pleased to hear it. Let us see whether you have learnt anything worthwhile with Mina, shall we? Do you have a piece of paper?’” The director approached my desk with a pen.

“Can you read this?” “Mina, you can move him up a class.” The word on the page was “revolution.” |

|

II Later that day, I was relaxing in the Niavaran Palace gardens, reading Franz Kafka’s The Trial. The palace has been out of use since the last Shah of Iran fled the country before the Islamic Revolution of 1979. It has been preserved as a museum ever since. As I was getting up to leave, I was joined by an old gentlemen and his family.I glanced over at them quickly. The mother and three daughters were wrapped in black chador, which they held shut with their hands, and bit pathetically to cover as much of their mouths and faces as possible. The father had a hard, stubbly face. He wore an off-white shirt (buttoned-up to the top, un-tucked, no tie) and a tattered pair of grey suit trousers that were too short for him. “Perhaps they support the regime,” I thought. I fixed my eyes back on the palace, and the father began to speak. “The revolution was a disaster. To think, we shed all that blood to overthrow the Shah for this!” I nodded silently. |

III You may have read Marjan Satrapi’s autobiographical comic Persepolis, or seen the film. I am often asked whether it accurately portrays the 1979 revolution, or life under the Islamic Republic. It is usually with a sense of both urgency and resignation that I respond, “Yes.”Iran is a totalitarian religious dictatorship. For the last thirty years, our government has blurred the lines between the state, civil society and the private sphere and has ruthlessly tried to control all three. Politics is loosely guided by Islamic ideology, largely according to the interpretations of one man – the unelected Supreme Leader. In the absence of the Hidden 12th Imam, he has the power to intervene in more or less all government matters. His decisions are insulated from the scrutiny of day-to-day politics. Iran has a farcical democracy. Parliamentary and presidential candidates are vetted by the unelected Guardian Council. Iran’s last presidential election in June 2009 is widely believed to have been rigged. Following the announcement of results, millions of Iranians marched through the streets asking for a recount–the largest challenge of government |

authority since 1979. You may have seen the pictures of basijis on motorcycles beating demonstrators and government snipers shooting randomly into crowds. In Tehran, demonstrators protest against voting irregularities following the Iranian Presidential elections in 2009. People took photos and videos using their phones and posted them on-line to reveal the size of the protests, which was played down by the government. They also sought to show that all the violence was caused by government security forces trying to crush the rallies. The demonstrators' faces have been blurred to conceal their identity. The regime maintains power largely by spreading propaganda via state-controlled mass media, restricting free speech, and keeping |

citizens under constant surveillance. In Iran, it is forbidden to challenge the legitimacy of the Islamic Republic. Newspapers critical of the regime are closed down. Access to information via the internet is blocked. Political opponents of the regime are imprisoned, tortured and sexually abused.Many prisoners either go insane or attempt suicide. After China, Iran has the highest rate of capital punishment in the world. Capital offenses include fornication, adultery, homosexuality, the consumption of alcohol, and denying the existence of God. Executions are carried out by firing squad, hanging, stoning, decapitation or flagellation. Criminals are sometimes executed in public. Iran permits the execution of boys slightly younger than 15 and girls slightly younger than 9. It leads the world in executing juvenile criminals. Women have unequal rights to men. They are legally considered non-mature and under male guardianship. Post-pubescent women are required to cover their hair and body in public. They need their husband's or father’s permission to work outside the home or leave the country. In court, the testimony of two women counts for that of one man. I once asked someone in Iran, who has four wives, what it is like to marry so many times. |

|

He said, “It is like buying the same copy of the same newspaper on the same day over and over again.” That was the end of our conversation.Iran’s human rights record has been criticized by virtually every single existing international human rights and intergovernmental organisation in the world. Iran’s response: we are not obliged to follow the West's interpretation of human rights.  A pro-government demonstrator swaps the common Iranian-Islamic manteau for a long leather jacket under a traditional chador.

|

IV Few people care about the miserable situation in Iran. Why would they when Iran’s international reputation is so deeply shrouded in controversy? Does Iran export terrorism? Why is Iran meddling in Iraq and Afghanistan? How close is the regime to building nuclear weapons?These days, humiliated Iranians simply watch from the sidelines as their president flouts opportunities for détente, instead calling for open debates on whether the holocaust ever happened, and declaring that “In Iran, we don’t have homosexuals.” Is it any wonder why so many embarrassed Iranians prefer to call themselves Persians?V This is depressing reading. I could write about Iran’s breathtaking nature, its glorious ancient empire, or its enigmatic and world-renowned poets and philosophers.Who, then, would focus on the harsh reality? Do I not owe my co-nationals in Iran this service? I too see Iranian protesters trampled in the streets by the Revolutionary Guard. I hear their cries for help on TV like you do - in my mother tongue. |

A women in a chador on a beach on Qeshm Island, Southern Iran. Why do I feel such a sense of duty towards Iran, as if the political baton was dropped at my feet? Millions of Iranians do nothing. Moreover, I am a British citizen, and associate strongly with this part of my identity. Yet, something still niggles in the back of my mind. One day, I know I will join the Iranian opposition movement in earnest. At the moment, I limit my activities. I publicize Iran’s injustices in the UK, write articles on reformism, organise conferences and help campaign organisations lobby MPs and run rallies in London. Risk-factor: medium. I have stayed away from Iran since June 2009. Look again at the facts above about the barrage of restrictions Iranians are under. Would you be |

brave enough to do more than I do? Would you stick your neck out for your country? People close to me have. It may be interesting for you to hear their stories.

VI My father became politically active as an undergraduate in Tehran University during the late 1960s. In those days, there was growing resistance against the Pahlavi Monarchy that preceded the Islamic Republic. A decade and half before, the United States had deposed our democratically-elected Prime Minister, Mohammed Mossadeq, placed him under house arrest until his death, and reinstalled Reza Shah as the sovereign king, after he had fled to Italy. From then on, the Shah had ruled the country illegitimately, as a lackey of the West, and with an iron fist.My father also learnt to operate print machines and distributed banned literature ... everything from Franz Kafka to With a group of activists, my father began organising student participation in anti-government demonstrations. These were violently broken-up by the SAVAK: the Shah’s secret police.Mao Tse Tung. |

|

On a number of occasions, the SAVAK sought revenge by pouring into my father’s student dorms and beating students with clubs. Undeterred by the dangers, my father and his friends started a political cooperative in Tehran University’s Economics Faculty. It assumed control of union responsibilities and boldly campaigned for the dismissal of faculty members closely aligned with the monarchy. My father also learnt to operate print machines and distributed banned literature to students and ordinary citizens who wanted to see what the government was keeping from them – everything from Franz Kafka to Mao Tse Tung. Years later, my father learnt that some of those he worked with were, in fact, SAVAK informers, who gathered information on who was printing the books and who was reading them. Between 1970 and 1971, many of my father’s friends joined Fedayeen guerrilla groups. Inspired by the revolutionary struggles of China, Cuba, and Vietnam, these fighters advocated violent resistance against the monarchy and trained in guerrilla warfare in the mountains outside Tehran. “One small spark is all Iran needs,” they would say. |

While they built small arsenals in their garages, my father kept his distance. But his expanding political portfolio meant that the secret police had already singled him out for arrest. After university, my father was conscripted into the national army. He taught in a remote desert city for two years, but after conscription, the government refused to certify that he had completed his duties. One of my father’s friends, Mahmoud, warned him that the SAVAK had a very extensive file on him. He was being watched. How did Mahmoud know this? Mahmoud confessed that his brother was Colonel Tehrani, one of the SAVAK’s highest ranking interrogators and most infamous torturers. Tehrani had told Mahmoud that he had prevented my father’s arrest because he feared this would implicate his brother. He advised Mahmoud to cut all ties. My father had already had one lucky escape. Two years into his degree, the SAVAK came looking for him in his apartment in Tehran. Luckily, he had gone home to Esfahan that weekend to visit his family. In frustration, the SAVAK arrested and detained his housemate for two days. My father had ridden his luck for long enough. He left the country and started graduate study in the UK. |

|

In 1983, my parents, who had married a few years earlier, both finished their studies in the UK and prepared to return home where they would continue their political efforts and start a family. That year, the Party headquarters in Tehran were raided. Like so many parties before them, Tudeh went underground. Dozens of my parents’ friends and colleagues were hunted down by the Revolutionary Guard and sent to prison. Some of them repented and were released years later. Others were summarily tried and executed by firing squad. Still others were never heard from again. The raid left my father completely naked. The Iranian government, embassy, secret police, border authorities; everyone knew exactly who he was and what he believed. If he went to Iran, he would not have even made it off the plane. My parents rented a tiny flat in London, hoping in vain that things would soon change. When my father applied to have his passport renewed, the government refused. Instead, it invited him to travel to Iran, where his request would be privately managed by the border authorities. My father used this invitation for arrest to secure permanent leave to remain in the UK as a political asylum seeker. In many ways, he says today, this was his ticket to safety. “In other ways, it was confirmation that I was to be another foreigner living in a country that they hadn’t |

truly chosen. With my broken accent and Iranian sensibilities, I would never be English, and no one would ever accept me as one. It is a lonely feeling. All I could think about for years was returning home. Everything in the UK felt temporary and transient. How can you start your life anew when you are always ready to drop everything and leave?” My father left the Party in 1991. In the throngs of petty internal rifts, and obsessed with revolutionary communism, members had lost sight of the real problems that affected Iran. My father put forward a motion to drop from the Party’s manifesto its commitment to Marxist-Leninism. The Tudeh party, he said, had found a prophet in Lenin, a bible in Das Kapital, and a religion in revolutionary communism. When the motion was not even tabled for discussion, my parents promptly resigned. Eight years later, my parents and I showed up at passport control in Tehran’s central airport. Border authorities immediately registered our long-term absence from the country. We were taken to the security zone for questioning. Hours passed. The longer we stayed, the more likely it became that they would find my father’s file.All of a sudden, an apparently lost traveller strolled into the questioning room. |

|

My grandmother had taken the rifle and buried it in her garden. When Reza was arrested the same day, he had confessed, under interrogation, that his rifle was probably in my grandmother’s possession. A few hours after Reza’s admission, my grandmother was arrested outside her home, blindfolded, bundled into a van and brought to Evin Prison. Still blindfolded, she was lead into an interrogation room and sat down. The guards then brought in my uncle.

“This is your son. We are going to kill him,” a voice said. “Mum, that thing I gave dad – they want it. Give it to them.” My grandmother was quickly thrown out of the prison. My grandfather, who had secretly followed the police van that abducted her to Evin’s door, was pulled inside. He knew nothing about a gun. The interrogators thought he was |

lying, so they detained him. Meanwhile, my grandmother dug up the rifle and threw it into the street. A few days later, it found its way to Evin Prison. Neither my grandfather nor my uncle was released. My grandfather was detained for one month in a 5x5 meter cell shared with 39 other men, with no news from his son or the outside world. Every day, he was interrogated about the no-longer-missing rifle. To soften up detainees before interrogations, the guards passed around a list of people who had died under torture.

“They had confiscated my glasses and wouldn’t give them back to me. For a month I could hardly see anything. Every day, I had to ask one of the inmates to read the list to me. I would start crying before they finished, waiting for them to say his name.” IX My uncle stayed in prison for the rest of his life. He was officially sentenced to seven years in prison, but he always knew that Evin was likely his final home. From the age of 21, his family and fiancée could only contact him once a week from behind a glass wall. |

|

He tried his best to keep their spirits up. “Dad, your hair has so much volume! What shampoo are you using?” Everyone would laugh, but the stress had taken an awful toll on my grandfather, who was in and out of hospital. My uncle would say that he was happy in prison – that he had done nothing wrong and that he was proud to maintain this under interrogation. Everyone tried their best to believe him. My grandmother recalls with pride how he used to march towards the visitor’s window every week – his hands cuffed, in a prison boiler suit – with his head held high, smiling confidently. When the guards addressed him, his smile would vanish. He looked them straight in the eye – something few prisoners dared do. “Sometimes, when I saw how strong he was, and how weak I had become’ says my grandmother,‘I wondered which one of us was the real prisoner.” My uncle chastised guards whenever they pushed prisoners around in front of their family. He once chastised a guard for speaking rudely to a visitor, right in front of the prison warden. Four years into the sentence, my grandfather pretended he was dying and asked for his son to be granted one day of leave to come home. |

The family flocked to welcome him. In the 8 hours he was home, he ate not one morsel of food and drank not one drop of water.

“How can I eat when everyone in prison is hungry?" he said to his parents. "When I die, it is they who will be your sons.” X Once, during visiting hours, in front of the prison guard, my uncle stood up and turned his back to the window, revealing to his parents the blindfold he was holding in his cuffed hands.“This is what they put on me before they start.” I can only imagine the horror my uncle endured in detention. The Islamic Republic is in a league of its own in its systematic use of torture. People who have served prison sentences under the SAVAK and the Revolutionary Guard, without exception, say that one month’s torture under the Revolutionary Guard aged you like a year would under the SAVAK. Consider the torture techniques used in Evin Prison: suspension from high walls and ceilings; cutting out pieces of flesh with the body tied to an iron bed; insertion of sharp instruments under the fingernails; submersion under water; mock executions; |

|

confinement in coffins; enforced ingestion of excrement; attachment of weights to genitalia; enforced intercourse between inmates. Withstanding torture has nothing to do with ideological zeal. It is about being unwilling to switch hats and join the enemy. Surely people would do anything to be released? To prove your remorse, the Revolutionary Guard forces you to denounce your beliefs in front of your inmates, to testify against them, to help them hunt down people on the outside, and finally to take on the role of torturer and executioner. Withstanding torture has nothing to do with ideological zeal. It is about being unwilling to switch hats and join the enemy. XI Seven years elapsed. On the week of my uncle’s release, the prison warden called my grandmother and said, verbatim,“Your son has died. Come and collect his clothes.” In the summer of 1988, in an act of unprecedented brutality, the Islamic Republic secretly and extra-judicially tried and executed thousands of young |

political prisoners. Nobody knows exactly how many were killed. Amnesty International has recorded roughly 4,500 certain dead. Most Iranian human rights groups estimate the total to be around 25,000. My grandparents were told to certify that their son died of natural causes if they wanted to know where he was buried. They refused. They knew the bodies had been piled in the hundreds on top of each other, probably in a dump unknown to most of the prison guards. The Islamic regime refuses to discuss what happened in 1988. According to official records, my uncle died of natural causes. I never met my uncle. Everything I know about him comes from my grandmother. My mother has never spoken to me about him. I have never even heard her say his name. XII Family histories like this are all too common in Iran. Most of the Iranians you know can tell you about someone with similar stories of discord with the government. Given my family history, is it any wonder that I work in politics? But, then, why am I in Palestine and not Iran? Perhaps the main reason is that Iran imposes these injustices on itself. If you are familiar with Iranian politics, you will know that we have been on a zigzag |

|

towards democracy for the past hundred years. The appetite for change is strong. In Iran, one small but significant portion of the population suffocates the rest. At the same time, for one reason or another, significant sections of Iranian society still support the Islamic Republic, still think that Iran’s head of state is God’s shadow on earth. Consider how, on the 10th and 11th of December 1978, during the Islamic month of Muharram, somewhere in the region of 7 to 9 million people marched in the streets demanding the resignation of the Shah and the immediate return of Ayatollah Khomeini. Even if we discount for exaggeration, that is roughly 10% of the population – perhaps the largest protest demonstration in history. Two months into Khomeini’s austere rule, 98% voted to replace the monarchy with an Islamic republic in a national referendum.True, some people who marched against the Shah also opposed Khomeini’s rule. It is also true that few people thought hard about what they were consenting to when they voted in the referendum. Nor, indeed, were they offered reasonable alternatives. Many supporters of the regime today depend on the status quo for their livelihood. Others are misinformed or brainwashed. Be that as it may, Iranians who say that the Islamic Republic has lost all support are |

deceiving themselves. In Iran, one small but significant portion of the population suffocates the rest. We have to look inside for the causes and remedies. Palestine’s predicament is completely different. It suffers largely at the hands of outside forces, and as a result of outside interference. Their plight deserves everyone’s full and immediate attention. In Iran, we make our own chains.   A pro-government demonstrator hands out posters. The poster reads 'Death to America'. |

| Ramallah, Palestine. An Oxford trained British-Iranian, the 7th Fortnightist maintained anonymity while publishing for Fortnight, due to restrictions on Iranians in the West Bank. His work for Fortnight was detailed in Blackbook Magazine and on several blogs. One of his pieces was republished by the Oxford University alumni press. After Fortnight he collaborated with Fortnightist Drew Zimmer. |