FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

A DEPARTING PUPIL OF PHILOSOPHY WEIGHS ABSTRACT CHALLENGE. ANONYMOUS DISCUSSES HOW HE GRADUATED FROM THOUGHT TO PRAXIS.

read the essay now >>

|

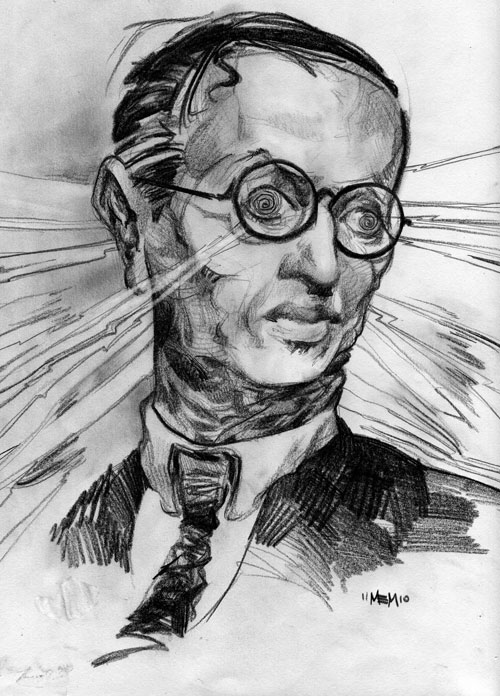

I One of my most memorable courses at university was on the philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre, partly thanks to my tutor. She was a scatty, slightly hunchback woman, with messy, grey hair that looked like the end of a mop. Her office was decorated with loose scraps of paper, empty wine bottles and lovingly-taken photographs of her thirteen cats. She slept on a sofa bed in her office, and wore pyjamas to all our tutorials.The most unorthodox thing about my tutor was her teaching technique. Explanation was not her forte, so instead, she made her students experience Sartre’s philosophy firsthand. One week, she asked me to write about Sartre’s thoughts on other people. Traditionally, philosophers have wondered how we can know that other people really exist. What makes us so sure that the people we perceive, who appear like us to be thinking and feeling, are not in fact robots, or something similar? Sartre’s answer is that we know other people exist because we feel their presence in such an intense way. Compare how it feels to share a room with other people and how it feels to share it with lifeless objects. Consider also what happens when two people’s eyes meet. Sartre says a war of sorts ensues. |

Each subject tries to turn the other into an object, with the aim of asserting themselves, and their dominion over the world they share. You may recall that it was Sartre who famously wrote the line Hell is other people in his play No Exit. That week, my tutor opened our discussion by cutting to the chase. "Have you ever felt the gaze of ‘the Other?’" Her eyes locked onto mine. She appeared frightened as she waited for my answer. She fidgeted and twisted her body, slowly shrinking into the corner of her sofa bed. She broke eye contact only to throw a few desperate glances in random directions.At first, I thought she was having an episode in slow-motion. Eventually, I realised I was in a Sartrean drama. I was the subject, and she was the object. We were at war, and I was stealing her world. Twenty minutes later, our roles reversed. That was the last time I brought a pen and paper to my Sartre tutorials. |

|

II Philosophy has many stereotypes. Perhaps the story above fits yours. Maybe you think of brainy kid logicians and complicated symbolic language; maybe, of bearded Greeks and reclusive geniuses.Behind these stereotypes lies a complicated philosophical question in its own right – "What is philosophy?" Some philosophers spend years trying to answer this question. Others rarely contemplate it in earnest. I hardly gave it any thought when I was a student. Eight years and two degrees later, I have become engrossed in the question. If you dig around, you will find two broad categories of answers. The first equates philosophy with its conventional subject matter. There are certain questions that the inquisitive mind finds naturally perplexing. These are said to lie at the heart of philosophy.

What really exists? |

For example, in business, philosophers ask, "What really is success?" In experimental science, philosophers ask, "Why think that like causes will have like effects?" In history, philosophers ask, "When does one event really end and another begin?" These various questions are organised into sub-disciplines. The central ones are probably familiar to you:

Metaphysics (the study of existence and reality) |

|

III The second common answer to the question of "what is philosophy" side-steps this problem. This time, the story goes that philosophy is a way of approaching questions. Philosophers are systematic thinkers. They break problems down, analyse and clarify key concepts, and build arguments using clearly-defined premises, all in crisp and straightforward language.The analytical method refers to a broad set of intellectual resources. For all their virtues, philosophers can hardly pretend to have a monopoly over any of them. People who are acquainted with philosophy will recognise this as a rough construal of the analytical tradition. The analytical method, as you can see above, refers to a broad set of intellectual resources. For all their virtues, philosophers can hardly pretend to have a monopoly over any of them. Students of countless disciplines aspire to these skills. No one will deny that critical thinking and forceful argumentation are qualities of good philosophy. But one hardly advances any subject with poor reasoning and half-baked ideas. |

Perhaps, then, this second account of philosophy is too broad because it fails to distinguish philosophy from other subjects. Or, is it too narrow? Look again. If we equate analytical philosophy with philosophy itself, how can we make room for famous philosophical traditions that do not fit neatly into the analytical straightjacket; like Hegelianism, Marxism and Existentialism? Much has been written about the merits and demerits of doing philosophy "analytically." The debate would hardly make sense if analytical philosophy was, by definition, the only game in town. We are not getting much closer to an answer. For those of you who are new to the subject, this is what it feels like to do philosophy. You take an idea you think you know something about. Upon reflection, it crumbles in your hand. IV I want to share with you my personal understanding of what philosophy is. I believe it constitutes the beginnings of an answer to our tricky question. There are interesting objections one could raise against my view. Typically, philosophers spend much time considering potential objections, and offering replies, in order to give greater weight to their theories. |

|

Given the context, I hope you will settle for slightly less – an introduction to my opinion on what philosophy is. It draws on the answers above, and captures what I think makes them attractive. One thing you might notice if you compare philosophical and non-philosophical questions is that there is usually a (more or less) universally agreed method of solution for non-philosophical questions, whereas for philosophical ones it is largely unclear how we should proceed. Consider the following:

Is this road a cul-de-sac? It is obvious how to answer the first question. Go to the end of the road and find out. For the second, just do the arithmetic. Scientific |

experiments reveal the answer to the third. As for the final question, asking Tony would be a start. Suppose he were to give you a frank and believable answer. And suppose that the answer was corroborated by his close friends, family and political associates. It seems you would have an answer that could at least garner consensus. There are some non-philosophical questions that we know how to answer but are unable to, because the agreed method is not at hand. Did Socrates have a favourite color of flower? What would be a good strategy for answering this question? Asking Socrates would work, if he were still alive. If there were reliable reports of his floral tastes, then we could do a bit of research.Neither avenue is available to us. However, the fact that we cannot answer the question does not mean we do not, in principle, know how to.Now consider some palpably philosophical questions.

How can we tell right from wrong? |

|

Unlike non-philosophical questions, it is unclear where to go in search of an answer. Take the first question. Should we seek guidance through revelation? Is it enough to know which acts produce the greatest amount of happiness? Might the answer be buried in our deepest intuitions? Can we perceive a property of "rightness" or "wrongness" in actions if we look hard enough? Every avenue has its merits and demerits. However we approach the question, we leave ourselves open to sweeping criticism. When people disagree about the solution to a problem and the method of investigation, philosophy is born. This happens in every field. In the natural sciences, mathematics, art, history, economics, film, etcetera, there are difficult questions and conceptual puzzles, and people have hazy ideas about how to proceed. This is why there is a "philosophy of..." almost every discipline. You will recognise some of the characteristic questions.

Does studying the human body reveal a human nature? |

What makes Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ a work of art? V Philosophy shares the space I am describing with other subjects. Art is a central example. We have all read novels and seen plays that explore what matters in life, what beauty is, the discrepancy between appearance and reality, freewill, and so on. What distinguishes philosophers from artists is method. Philosophers typically prefer a slow, overtly intellectual, and systematic meander into the unclear. This is why I think good art usually makes for bad philosophy. And the art is no weaker for it. Artists can attend to the same |

|

dilemmas that philosophers explore with great sophistication. Art and philosophy share the space I am describing. But they are not rivals. Some thinkers have garnered acclaim from academic philosophers and artists alike, like Jean-Paul Sartre. Others have fared less well. Opinion in academic philosophy is divided when it comes to the likes, for example, of Jacques Derrida, Gilles Deleuze or Jacques Lacan, with whose works you may be familiar. For some, they are amongst the most original thinkers of the last century. For others, their work exhibits poor argumentation, wildly exaggerated claims and deliberately obscure prose. Continental philosophers often write in a style that is evocative and performative. Analytical philosophy sometimes looks like the boring older brother. Like many others, I am somewhat uncomfortable with the mysticism surrounding Derrida, Deleuze and Lacan’s work, and the orgasmic response it provokes amongst their admirers. But I do not deny the richness of the very loosely dubbed "continental philosophy," which is the broad tradition in which these thinkers flourished. Continental philosophers often write in a style that is evocative and performative. They challenge |

the status quo through what they say and how they say it. Analytical philosophy sometimes looks like the boring older brother. Or, it smacks of pointlessness – a bit like continually sharpening a pencil, but never getting round to using it. I leave the final judgement on the relative merits of analytical and continental philosophy to others more knowledgeable than me. For my part, I offer a modest defense of a philosophy that cherishes brutally clear arguments, conclusions drawn from carefully defended premises, and non-lyrical, almost clinical prose. Philosophical questions are hard, and we are uncertain about the conditions for a right answer. They are also quite basic. There is not a lot you should assume or take for granted, and this includes the intellectual resources you are using. We ought not to compound these problems with complicated writing and obscure arguments. We would do better to avoid any hint of confusion. I confess that I started university wanting to read and write rousing philosophy that revealed deep meanings where others thought there were none. In my first meeting with one of my philosophy professors at university, I was told: |

|

"Every week, you will complete two 2,000 word essays. If you cannot make your points quickly and in simple sentences, they are probably false." How narrow-minded, I thought at the time. A few years down the line, I was teaching my students to write up philosophy essays almost like a science experiment.VI People often ask whether philosophy has any point. Why should we bother with it when we are still trying to answer the same questions intellectuals posed centuries ago?Most people agree that individual philosophers gain skills inpersuasion, problem solving, abstract thought, and sniffing out sugar-coated nonsense. But does philosophy serve anyone else? I think that the grander achievements of philosophy only become obvious when we think about them in certain kinds of ways. Philosophy endeavours to shed light on how we can answer abstract questions. When it achieves this goal, it ushers itself from the scene. Once we know how to answer a certain kind of question, it is no |

longer the domain of philosophy. Consider where rain and sunshine come from.This was once a philosophical problem. Consider where rain and sunshine come from. This was once a philosophical problem. Now, it is properly a part of geography, meteorology, or more generally the natural sciences. We know why the sun shines one day and why it rains the next. We know how to predict the weather, even when the necessary equipment is out of our reach. Likewise today, many parts of the philosophy of mind are being handed over to cognitive- and neuroscience.We could count all of these as further examples of science’s great achievements. I like to think of the advances as gifts from philosophy. After all, the first scientists who searched for methods to explain the weather were philosophers. One of them was Aristotle. And in his day, science as we know it was called "natural philosophy." |

|

VII Some branches of philosophy appear destined to stay in philosophy. Moral and political philosophy is one example.

What are the ultimate ends of life? |

VIII Moral and political philosophy can be more than just a personal pastime. When doctors and nurses care for the sick and needy, do they not achieve great things, even if they get no closer to eradicating disease once and for all? When politicians prevent a war, have they not accomplished something good, even if wars continue to rage elsewhere?We should think about achievement in moral and political philosophy in the same way. Pondering the demands of morality rarely, if ever, leads to definite answers. But it can help us understand, and therefore tackle, some (more or less) agreed real world problems for a while, like certain cases of systematic mistreatment of women, use of children in armed conflicts, and exploitation of the most vulnerable workers. We can accomplish great things when we reflect on what we owe one another, even when we get no closer to dispelling radical doubt about the fundamental nature of morality itself. |

|

IX I recently left academia. I spent two years as a graduate student and a term as a moral philosophy tutor, and somewhere along the way I learnt that I find research lonely. After a few months of pouring over the same books and articles, I lost sight of what was at stake, and struggled to see the forest through the trees.The Gaza war was the turning point for me. On December 28, 2008 I was on holiday in Bali, getting ready for breakfast in my hotel room. The television was on in the background when I heard the sound of explosions. Perched on the end of my bed, I glared at the playback of yesterday’s bombs falling on Palestine. I forgot all about breakfast and spent the whole day watching the news.

How many people have died? |

X Every real world problem has philosophical dimensions. Take the present subject of my advocacy work in the West Bank – the Israeli army’s persistent use of Palestinian children as human shields in military ground operations. There are difficult conceptual puzzles latent in this war crime. We might ask how young someone has to be to really count as a child, or how much physical danger has to be forced on someone for them to count as a "human shield."The world surely benefits when scholars debate these intricacies. Lately, I have been less interested in these philosophical details. To my mind, it is certain that the world would be a better place if things like this stopped happening. For the moment, this is my goal. I leave the philosophy to someone else.  |

| Ramallah, Palestine. An Oxford trained British-Iranian, the 7th Fortnightist maintained anonymity while publishing for Fortnight, due to restrictions on Iranians in the West Bank. His work for Fortnight was detailed in Blackbook Magazine and on several blogs. One of his pieces was republished by the Oxford University alumni press. After Fortnight he collaborated with Fortnightist Drew Zimmer. |