FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

BRED AND EARNED

BRED AND EARNED

IN PITCH BLACK, NINA BREEDS MICE TO MATCH. CAMARADERIE SUPPLANTS ISOLATION IN THE LEARNED CRAFT OF CLONING.

read the essay now >>

IN PITCH BLACK, NINA BREEDS MICE TO MATCH. CAMARADERIE SUPPLANTS ISOLATION IN THE LEARNED CRAFT OF CLONING.

read the essay now >>

|

I I work at the Jackson Laboratory.* Nicknamed JAX, it is located in idyllic Bar Harbor, Maine. Clarence Cook (“C.C.”) Little founded the lab in the early 20th century. Little’s legacy resides in his pioneering the technique of generating inbred mouse strains suitable for use as scientific research models. Aside from his extensive lobbying for the use of inbred mouse strains as a cancer research tool, C.C. Little’s legacy in pop culture resides in the fact that he is the obvious inspiration for prominent Maine children’s author E.B. White’s character Stuart Little—an anthropomorphized mouse. Little first expanded and applied Mendel’s laws of inherited traits to mice, and therefore bred mice for specific traits, such as coat color. He next developed a system of successively inbreeding the mice for many generations. Eventually, after breeding the mice continuously in this manner, all arising individuals will be nearly genetically identical. This was a tremendous leap for biological research, as all differences due to genetic background between independent mice could finally be zeroed out and controlled for. Over time, there would appear mice that bore phenotypically different traits than their litter-mates; traits ranging from non-detrimental—such as kinks in the tail, or |

Over time, there would appear mice that bore phenotypically different traits than their lopsided ears—to life-threatening, such as cancer and diabetes susceptibility. litter-mates; traits ranging from non-detrimental —such as kinks in the tail, or lopsided ears— to life-threatening, such as cancer and diabetes susceptibility. These differences were the result of spontaneous genetic mutations. Before the murine genome was sequenced, many of these spontaneous mutations found that substrains of mice were studied in the context of their resemblance to human diseases and disorders. Spontaneous mutations still occur in inbred strains to this day. In fact, they do so at such a rate that a JAX® process, the deviant search, is performed on a bimonthly rate for any mice that bear traits that deviate from those their strains stably express. The mice obtained from the deviant search will be catalogued, and an email will be sent to the entire research staff (myself included) that details the characteristics of each mouse selected for the deviant search. On the day of the deviant search, a message over the internal P.A. system will declare the deviant search and the time and location of its occurrence. |

|

For the listening JAX insider, this precise and earnest message can often sound humorous. II Over time, with advances such as the completion of the human and murine genomes, scientists were able to create targeted gene knockouts using inbred strains of mice, and develop mice that custom-fit human diseases and pathologies. Today, JAX® mice are heralded as the gold standard within the biomedical research community, and are both the most characterized and published mouse models in the world. What began as Little’s Maine pipe dream has flourished into an internationally-acclaimed and sourced industry; one that is widely used by research teams around the globe. Today, half of the Jackson Laboratory’s core facilities in Bar Harbor are devoted to the production, characterization, and exportation of custom mouse orders. The other half is a designated research facility, which houses the diverse research of over 40 principal investigators (or PIs). The PIs range from developmental, metabolic, and cancer to reproductive biology, among others. I work in the research facility under the guidance of one of the lab’s PIs; my technical title is “Research Assistant”. I function as a pair of hands in the lab: the pair able to |

execute multiple experiments at a time, and that have the associated mental and manual dexterity to analyze and interpret the collected data therein. ...My lab space, located in the oldest research building, has no windows or any inlet of natural light whatsoever. This process can feel isolating at times; however, it is both a collaborative and independent process. Collaborative, because before I set out to set-up any experiment, my boss and I will have discussed previous data and concluded what experiments come next. Aside from the input I receive from my boss, after I have an experimental design in place, my other colleagues, who may have years of experience with certain techniques than I, are always available and willing for consultation—which is especially comforting when approaching novel assays. My job is also independent, because when it comes to executing the experiment, it falls to me to organize, implement, and often times troubleshoot in order to ensure the experiment is working properly. My workdays have assumed a rhythm over time: I wake up at around 6:00 A.M., and take around 30-60 minutes to get ready for work. I hop in my Subaru and drive to work, which takes about 5 |

|

minutes. Against the backdrop of Acadia National Park’s pine-studded cliffs and climbing trails, the layout of the lab definitely stands out. The research facility has different buildings that are all connected. Its newer buildings have a more modern design and contain large, glassed-in atria that let in copious amounts of sunlight and scenery. Once I swipe my Jackson Laboratory identity keycard to gain entry into the lab, I begin to lose touch with the outside world. This is partly due to the fact that my lab space, located in the oldest research building, has no windows or any inlet of natural light whatsoever. In fact, many experimental processes I implement require little to no light due to light-sensitive reagents, so there are entire days where I am working in close to total darkness; making my lab feel subterranean, although it actually is on ground level. Once I get settled and check my email, I plan my day around which experiments I plan to set up, and then begin the preparatory work of compiling all reagents, solutions, and tools I will need for each experiment. After that, I begin the experiment, which could take anywhere from an hour to 4 or 5 hours to set-up, depending on the assay. Although it may not take too long to finish an experiment (there are days when I feel that |

robots could do the work I’m doing, and indeed they may be able to in the future), the real difficulty lies within perfecting the technique. III One of the major objectives in any scientific pursuit is to control all variables that may confound the resulting data, and all experiments should be designed accordingly to prevent that from happening. One of the hallmarks of hypothesis-driven research I have learned over time is that, no matter how controlled and well-planned an experiment may be, an unimaginable number of events can happen which can render an experiment null and void. For a simplified example, suppose you set up an experiment checking for a specific DNA segment within experimental samples. You’d want to include a negative control—something like water, which should contain no DNA—and a positive control—a sample you know would bear the DNA segment in question—alongside your experimental samples. You could set up the experiment from start to finish, and get to your end result and see no corresponding DNA segments in any of the samples, either control or experimental. Because you included a positive control, this informs you that something went wrong somewhere along the lines of the set-up. |

|

Perhaps the input DNA concentration is too low. This kind of problem happens all the time, and when dealing with an experimental technique that may take five days from set-up to completion (and the wherewithal to know if the technique has worked properly or not), it becomes a necessary trick of the trade to be able to A) accept this temporary failure and B) correct and troubleshoot it as soon as possible. In the middle of the day, either during, or between experiments, I take a 15-60 minute lunch break—usually at the cafeteria at JAX, where the atmosphere is often more interesting than the food. Here you will see PIs conversing with fellow scientists and non-scientific employees alike. But usually, like pair off with like: Principal investigators dine with other principal investigators, PhD students dine with other PhD students, research assistants dine with other research assistants, animal caretakers dine with other animal caretakers, and so on. Although the science-minded set of employees is not instantly visually apparent (no; we don’t dine in our lab coats), over time, it becomes easy to recognize the lab’s scientific set. As both an objective observer, and a subject myself, I wouldn’t say we are exactly socially awkward, but we tend to be individuals who have a million thoughts in our heads at one |

moment—especially during work hours. These can range from concerns about proper experimental conditions (What pH should buffer A be?), to worries about grant proposals and research paper deadlines. There are also, of course, all the concerns of non-lab life. I'm still pretty 'on the fence' about whether or not they could ever resuscitate a human from this ordeal without a steady dose of morphological deterioration, and/or extensive brain trauma. If I have another experiment to set up, I spend the rest of my day working on that. If I don’t have any other experimental set-up to perform, then there is never a shortage of things to do around the lab to fill my time: After going through the protocol and completing the experiments, the next step is to actually assemble the data so it can be put in a presentable form; usually, this entails long time spans spent in front of a microscope, or a computer screen, summing data on excel spreadsheets. It is also my responsibility to maintain the inventory for my lab and process all the out-going orders for reagents and materials. In between these periods of extreme mental concentration and functioning, there are moments where my colleagues (who have their own work |

|

to wade through) can tell jokes with one another and loosen up a bit. Our lab’s favorite escapist retreat is watching mindless YouTube videos, or engaging in somewhat humorous, somewhat science dork conversations, like on the state of human cryopreservation. (Side note: According to Wikipedia, the first human was cryopreserved post mortem in 1967. This individual was perfused with DMSO, the same cryoprotectant I use to cryopreserve cell cultures when not in steady use. Although great for what I do, if there was any possibility that individual could be thawed out, his brain would be totally gone… Even though they claim to use more advanced cryopreservatives, I’m still pretty "on the fence" about whether or not they could ever resuscitate a human from this ordeal without a steady dose of morphological deterioration, and/or extensive brain trauma.) Each step of any experiment has a completely logical and technical explanation. For instance, I can briefly summarize the technical events of one technique that I employ regularly, called fluorescence-activating cell sorting, or FACS for short, complete with jargon you may not understand. |

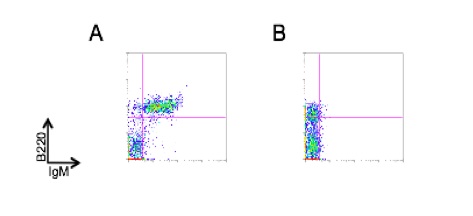

First, you begin by obtaining a heterogeneous mixture of cells. Next, you apply an antibody that binds to specific cell-surface receptors or markers of the specific cell type you would like to isolate, these antibodies are directly conjugated to a fluorophore that has a characteristic peak excitation and emission wavelength. After letting the antibody label the cells, you run them through a machine that emits laser light wavelengths that will excite the fluorophore conjugated to your antibody, and in real time, the percentage of cells labeled with your antibody will be shown on a computer screen connected to the machine the cells are flowing through (see Figure 1 for a sample of FACS data). Although I know in technical terms what is occurring every step of the process, I still can’t help but find a sense of magic and wonderment that in a short time span I can separate discrete populations of cells from a mixture of cells. It is that sense of wonderment that makes the mental drudgery of performing experiments totally worth it for me, and part of what inspires me to come in everyday and repeat my routine. This is a general outline of what my days in the lab are like. The truth about doing research is that |

|

schedules and workflows are always changing. The outcomes of the experiments being done in the present will directly affect what experiments come, and which hypotheses need to be tested, downstream. Unlike a standard job with hours set by the institution, it is the changing experiments that predicate when and how long one needs to be present for each day. IV I feel in research there is almost an unwritten rule, or a code of honor, that one must almost nullify oneself to work long hours, and over weekends — time that one certainly won’t get paid for — all in the pursuit of collecting data in a timely manner and perfecting technique. There is good reason for it, though, as being “scooped” — the act of another research group publishing information you are actively testing, and eventually wanting to publish on before you can— is a real threat in today’s information age. The Internet has changed not only how scientific news is processed, but also its accessibility. Instead of having to subscribe to exclusive periodicals, most publications are available at the click of the mouse through search engines.Within the scientific community, this means that whatever field you are working on, all published information is available instantaneously, and therefore, with any novel insights you may have, there could be |

there could be numerous research labs that have the same conclusions, and are working on the same concepts. In this aspect, completing novel experiments can be a real race against time. However, ultimately, it is this drive and commitment to the work that leads to breakthroughs, advances—and, hopefully, cures. Personally, I am committed to my work because I value the very plausible possibility that the experiments I so diligently work out may ultimately end up being a vital part of what shapes our knowledge on biology. What originates from my hands could shape future knowledge of the entire world.

|

| Nina lives and works in Bangor, Maine. She is a research scientist at Jackson Laboratories, a genetics lab. Fortnight was the first journal to publish her essays on immunology and breeding mice to identify cancerous defects. Nina continues to work at Jackson Laboratories, and has now co-authored papers published in top science journals, such as Nature Immunology. She splits her personality between science and music, as described in her work on Fortnight. Her band, Coke Weed, recently recorded and released their second album and will be opening on tour with The Walkmen. She says of her time with the journal, "I stand for everything the Fortnight mission embodies; I believe that our 'millennial' generation has all the tools to profoundly change our world as we know it. I feel honored to be among the ranks of my fellow fortnight contributors, and hope that my essays will inspire others as they find their own path in this dynamic world." |

Figure 1. Fluorescence-assisted cell sorting data:

Shown are representative dot-plots from two separate spleen samples stained with antibodies that detect B220, an early B-cell marker, and IgM, a surface antibody expressed on the surface of B-cells later in development. A) Control (normal) splenocytes. B) Experimental splenocyte sample showing different staining pattern (namely, no B220, IgM double positive population). Vertical axis represents number of B220 labeled cells; horizontal axis represents number of IgM labeled cells.