FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

A SCIENTIST RENDERS

A SCIENTIST RENDERS

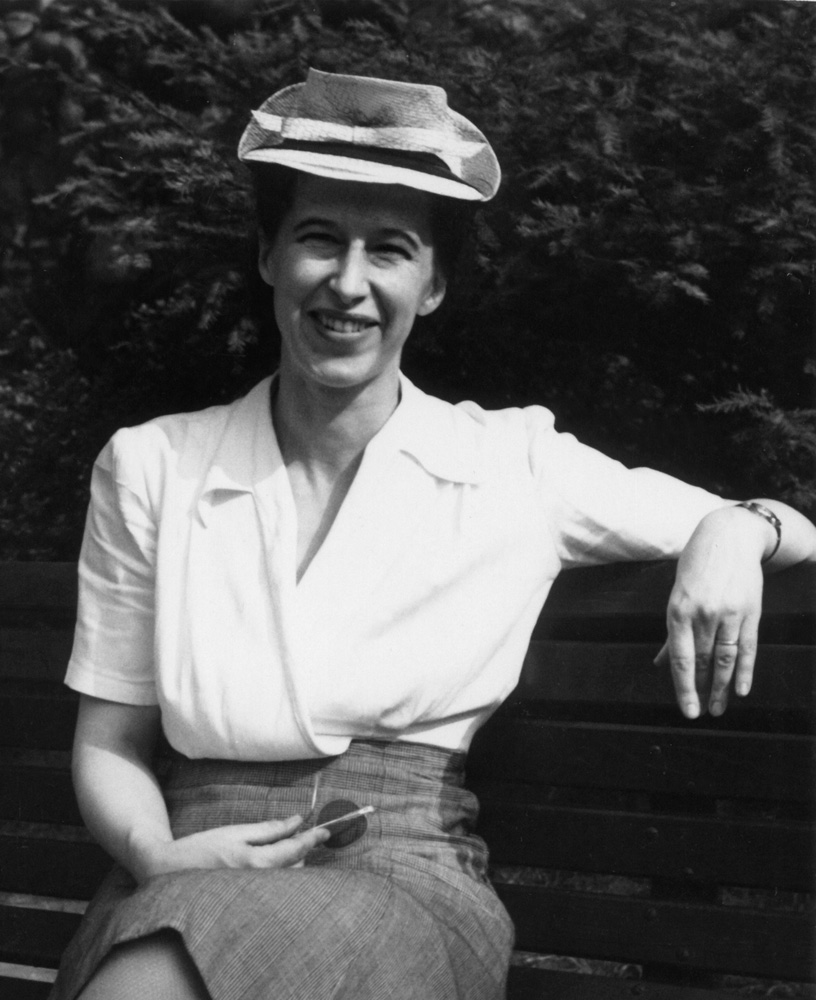

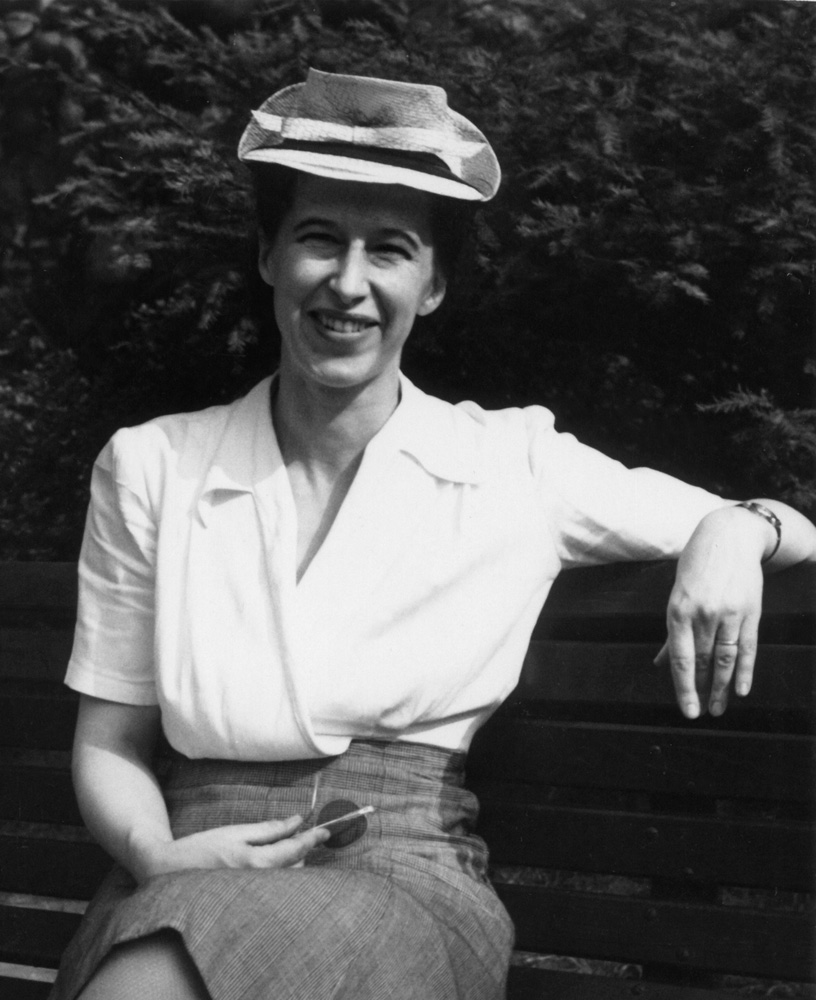

DORCAS HAGER PADGET BRIDGED SCIENCE & ART.

MEDICAL ILLUSTRATOR JARED CELEBRATES A PIONEER.

Read the essay now >>

DORCAS HAGER PADGET BRIDGED SCIENCE & ART.

MEDICAL ILLUSTRATOR JARED CELEBRATES A PIONEER.

Read the essay now >>

|

Dorcas Hager Padget, born 1906, started her career as a medical illustrator who specialized in neurosurgical illustration. Her illustrations remain masterful works of art: thoughtful, precise and exquisitely rendered. Hager Paget was the oldest of three sisters raised in Albany, New York by a former schoolteacher and a clergyman who promoted ideals of self-control and service to others. During high school, Hager Paget showed great interest in biology and illustrated a botany textbook with teacher Ada Wadler. Hager Paget accepted a grant to attend Vassar College with the idea that upon graduation, she would support her two sisters’ educations. Her acceptance into its honors program in 1923 allowed her to attend laboratory courses. She took a course in zoology where professor Aaron Treadwell allowed her to assist in illustrating a textbook. She also began traveling from Poughkeepsie into New York City to take figure-drawing courses. Later, Padget would transition to a career in science as a neuroembryologist, authoring numerous papers on congenital malformations of the nervous system. She was a pioneer in visualizing the complex development of embryological vasculature. Her transition from illustrator to scientist was accomplished in an era where women met resistance entering the male-dominated fields of science and medicine. |

More amazingly, she accomplished all of this without a bachelors or graduate degree. She accomplished all of this without a bachelors or graduate degree. Professor Treadwell at Vassar admired Hager Padget’s illustrations and decided to introduce her to the Art as Applied to Medicine department at Johns Hopkins. In the early summer of 1926, Hager Padget wrote to Max Brödel, director and founder of the Department Art as Applied to Medicine, suggesting that she would leave Vassar one year early to take a course in medical illustration. Brödel wrote her back saying she should finish her degree and apply. Hager Padget responded in August, sending along drawings she had done in the laboratory.Brödel reconsidered her application. He knew that Dr. Walter Dandy, a brilliant vascular neurosurgeon at Johns Hopkins, was in need of an illustrator. Brödel said that if Hager Padget qualified for the position, she would be allowed to work on a stipend at the end of her first year, and possibly assume a full-time position after graduation. Hager Padget left Vassar without graduating.1 “The exceptional pupil of this Group is Miss Hager. She is a Vassar girl and very gifted both |

|

in science and art,” wrote Brödel in his 1926-27 annual report to the Johns Hopkins University President. He went on to state that she qualified to work with Dr. Dandy by studying “with enthusiasm and splendid success.” Walter Dandy hired Hager Padget for full-time work at a salary of $2000 per year (Brödel’s recommendation) which was a moderate sum considering the average wage was $27 a week (approximately $1400 per year).2 Hager Padget could send her little sisters to college. Like many illustrators of that era, she worked mostly in the operating room. Her illustrations from this time expose her genius for rendering technique, design and storytelling. She was evidently learning a tremendous amount about neuropathology and neuroanatomy. Like many illustrators of that era, she worked mostly in the operating room, standing behind Dr. Dandy while he performed surgery. She made many quick sketches and took notes regarding the case then used them to create a refined illustration. Many of these illustrations were used in Dandy’s book Surgery of the Brain. She became one of the leading medical illustrators in the country.3Because of my current position in neurosurgical illustration, I am fortunate enough to have access |

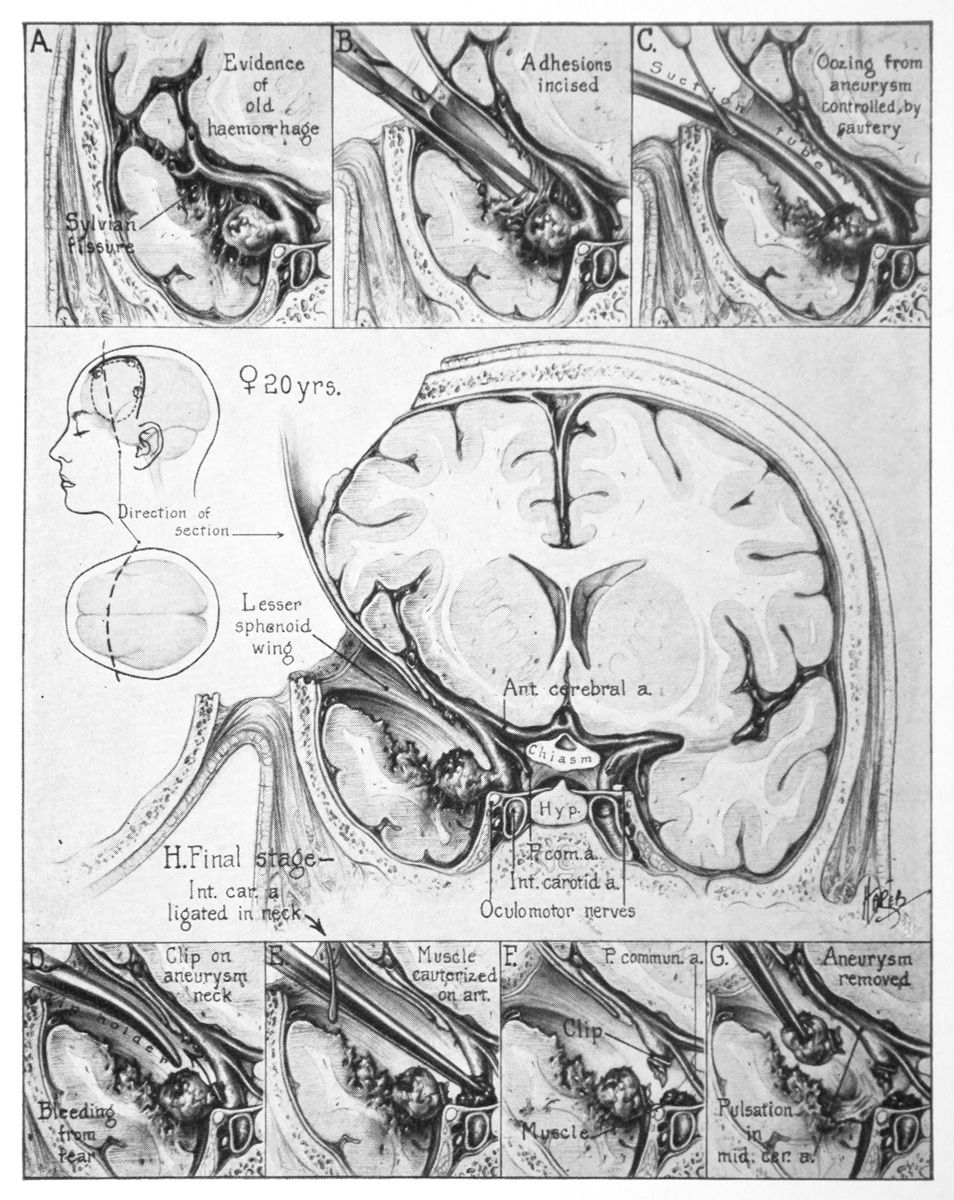

to a copy of Dandy’s book The Brain, an updated and reprinted version of Surgery of the Brain. It is filled with illustrations that demonstrate a thorough understanding of anatomy, a sensitivity with the medium and a deftness of storytelling. Hager Padget’s illustrations produce an almost instantaneous understanding of the procedure, while also allowing dense details to slowly wash over the viewer. As I see it, Hager Padget employs three components that make her pieces exceptionally successful: didactic quality, exquisite rendering and elegant design. All her illustrations contain these elements, but I have chosen three that I think exemplify each talent individually. This first illustration, of the surgical treatment of a ruptured internal carotid artery aneurysm, stands out for its exceptional didactic qualities. |

|

I am instantly struck by the central image It not only shows all the relevant anatomy but also teaches the nuances of that procedure. I am instantly struck by the central image and the density of information. We see three standard views of the patient for orientation. The two smaller views from the side and from above give enough information to orient the viewer to the third, larger view. The heads and brains are perfectly aligned, showing the craniotomy and a dashed line where the coronal section occurs. We also see the patient’s sex and age in text directly adjacent to the smaller heads.and the density of information. This technique of weaving text into the illustration was a hallmark of Hager Padget’s illustrations. The larger central image sets the stage for the top and bottom rows. It reveals the relevant anatomy along with proper placement of the brain retractor. This illustration encapsulates Hager Padget’s ability to take a very complex subject and break it down into teachable moments. Hager Padget’s rendering ability was exceptional. She was able to replicate textures in copious detail without losing her touch as an artist. |

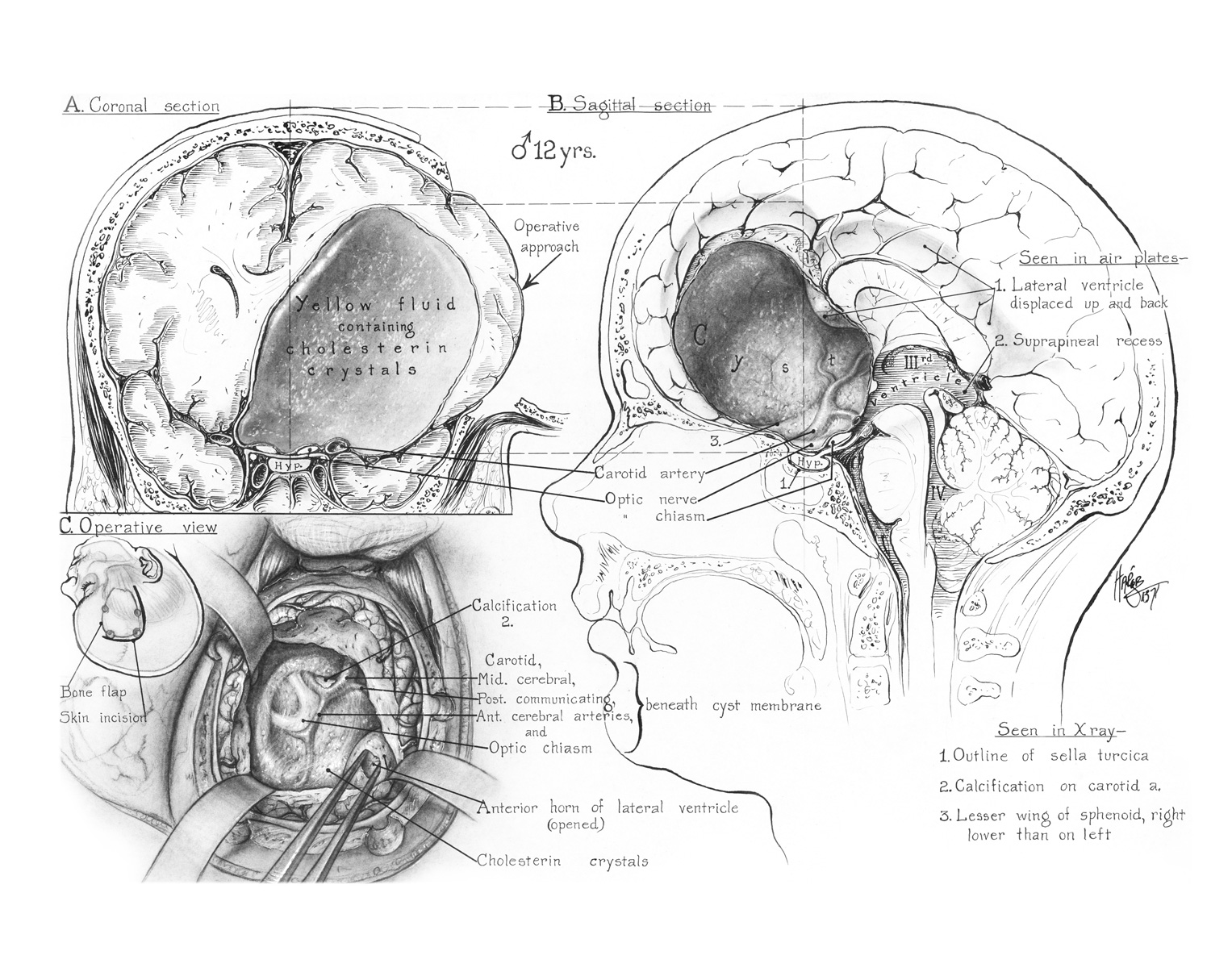

This illustration shows an enormous hypophysial duct cyst which extends up into the frontal lobe. It displays her thoughtful design and didactic talents by showing not only a coronal and sagittal section, but also the positioning of the head with incision, craniotomy, and the surgeon's view during the procedure. But the focus of the piece is the beautifully rendered cyst. The light reflects and refracts as it passes through, describing its texture, viscosity and opacity. But the cyst only begins to breach the artistic depth of this piece. The image on the left shows the cyst and brain cut sagittally. It interweaves precise but |

|

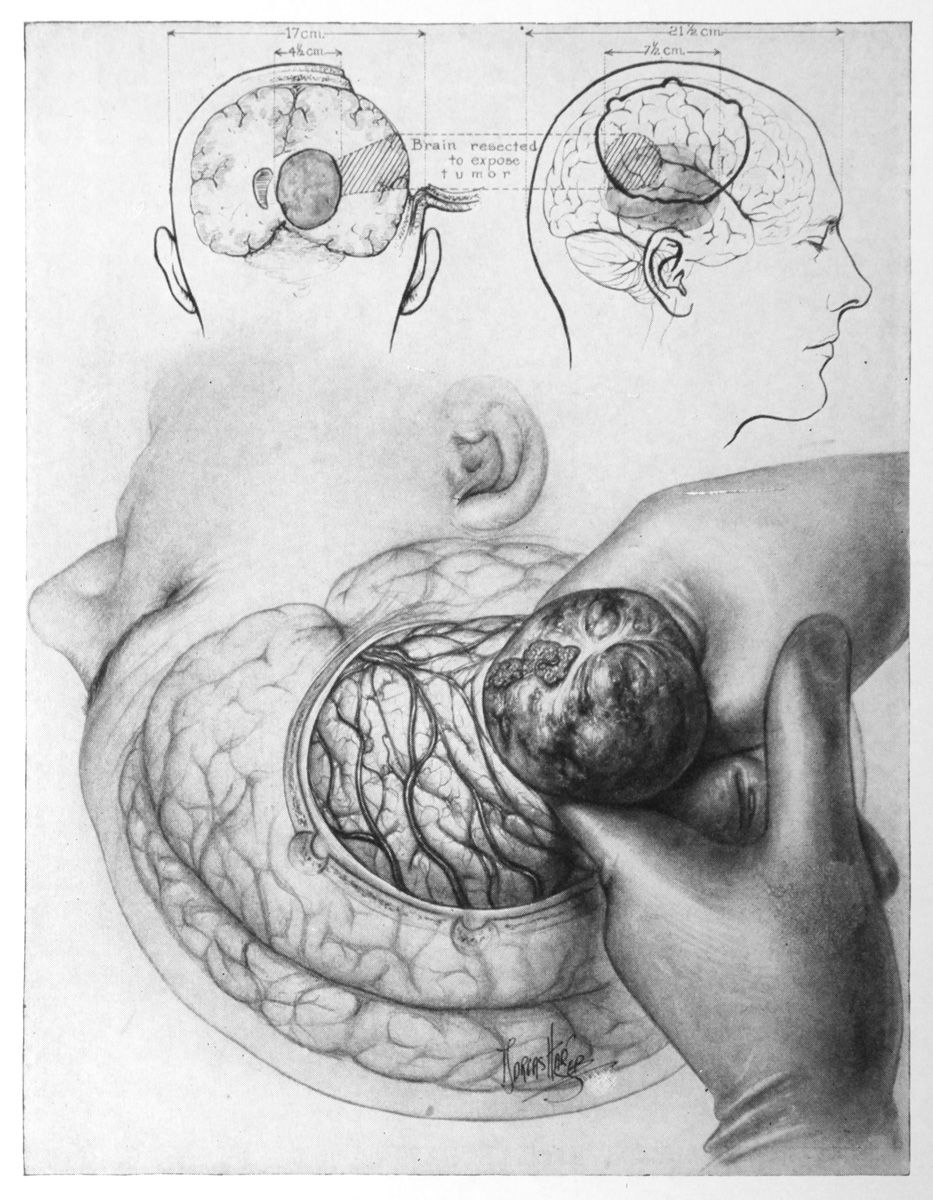

loose pen and ink strokes with detailed tone renderings. From a distance the architecture of lines form the muscles, skin, fat, bone and brain with precision and detail; but if you look closely, you can see how loose the pen work becomes. These marks are unique and show the hand of the artist. Great design in illustration takes careful thought and planning. This illustration describes the removal of an ependymal tumor from the right lateral ventricle. It has a beautiful, quiet and elegant design. Starting at the upper left corner, our eyes easily make a full clockwise circle. The figure on the left shows a minimal line drawing outlining the |

shape and location of the tumor. Hager Padget uses hashed lines to indicate the region of the brain to be removed. Dashed lines along with the craniotomy and skin flap move our eyes to the right where we see the tumor and brain removal in overlay. We begin to move down to that figure’s face, down through the chin and into the glove of the surgeon. As we sweep by the tumor and brain, we flow through the gentle fade of the patient’s face back to our starting point. Using size, contrast, and level of detail the illustration establishes a hierarchy of importance, as well as an order of understanding. The illustration establishes a hierarchy of importance, as well as an order of understanding. Hager Padget worked at Hopkins for 22 years in the same desk she had used as a student. Over time, she was less interested in just making beautiful pieces of art and became more interested in research. After Walter Dandy’s death in 1946, Hager Padget shifted gears and began to work for the Carnegie Institution of Washington in Baltimore.It was here that she did some of her most research-intensive and well-known work. She was tasked with describing the fetal arterial development by |

|

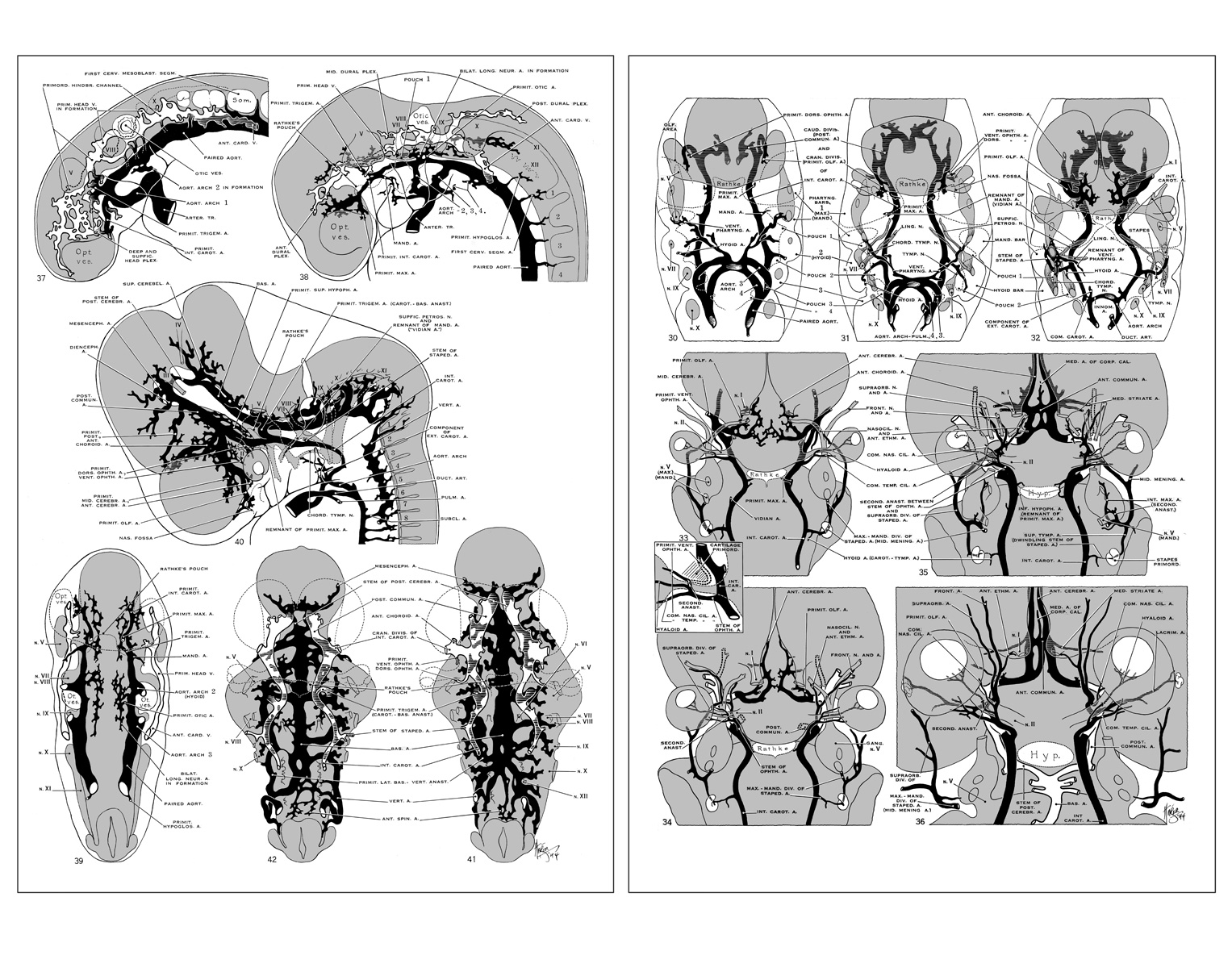

tracking the vessels through 22 separate embryos, ranging from 3.5 to 7 weeks.

The monograph for arterial development was published in 1948 and was a significant step in the field of neuroembryology. Hager Padget attributed this to the improvements in the development of contrast injection dyes.4 This publication spurred her to move forward in science and with a grant from the Life Insurance Foundation and, aided by her fellowship at the Carnegie Institute, she was able to create and publish a companion piece that described fetal venous development. To me, the incredible thing about these monographs is that for the amount of detail and |

accuracy required, they are still executed with beautiful simplicity. Hager Padget adds dimensionality to the vasculature by using stippling and hashed lines that describe structures located inside the brain and behind the eyeball. This series of illustrations is a masterful execution of both intense scientific research and elegant medical illustration. This series of illustrations is a masterful execution of both intense scientific research and elegant medical illustration. Hager Padget concluded the majority of her work on neuroembryological cerebral vasculature development at the Carnegie Institute and went in search of new research opportunities. In 1952, Dr. James G. Arnold, Jr. at the University of Maryland School of Medicine Division of Neurological Surgery hired Hager Padget as a “research assistant”—a title she chose for its ambiguity.She wanted to shake off the idea that she was simply an artist. But her lack of credentials caused difficulties when corresponding with others in her research field. She worked around this issue by only signing correspondences with her name, no title. The other researchers would assume she was a doctor and would respond to “Dr. Padget.” |

|

Her lack of credentials also caused her problems in her lab research. She was working with a pathologist on cervical spondylosis, using intact, sectioned human brains. During a research session, she commented in the pathologist’s presence that she believed one specimen had been misdiagnosed. Unbeknownst to her, the diagnosis had been made by that pathologist, upsetting him and leading him to say, “Why don’t you get an M.D. instead of trying to start at the top!” Hager Padget had struggled with cancer beginning in the early 1950s. She published articles on nervous system and neural tube malformations, including one that challenged the idea that spina bifida was solely caused by incomplete neural tube closure. In her research of the Arnold-Chiari and Dandy-Walker syndromes, she coined the term “neuroschisis,” which described abnormal clefts in the neural tube.Hager Padget had struggled with cancer beginning in the early 1950s. She had a mastectomy in 1955 and was later diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a cancer of the plasma cells in the bone marrow. Despite health problems, she continued her research until September 15th 1973, when she passed away at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. |

In my eyes, Dorcas Hager Padget’s work is nothing short of genius. Her thoughtfully designed illustrations tell a story in a clear and precise way while displaying her exquisite artistry. She set the standard for neurosurgical illustration and her effect on the fields of neurosurgical illustration and neuroembryology are still felt today.  *** Jared Travnicek is a medical illustrator based in Indianapolis, Indiana. He currently works as a neurosurgical illustrator at Goodman Campbell Brain and Spine. He holds a Master of Arts in Medical and Biological Illustration from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and a BA from Iowa State University in Biological and Pre-Medical Illustration. Jared is an award-winning member of the Association of Medical Illustrators. His website can be found by clicking here.For references, please scroll to the next page. |

|

REFERENCES 1. Kretzer R.M. B.A., Crosby M.L.A., R.W., Rini M.F.A., D.A., Tamargo, M.D., R.J. (2004). Dorcas Hager Padget: neuroembryologist and neurosurgical illustrator trained at Johns Hopkins. Journal of Neurosurgery, 100, 719-730. 2. Wolman, L. (1936). The Recovery in Wages and Employment. National Bureau of Economic Research, 63, 1-12. 3. Padget, D.H. (1973). A few research-career fings from no-degree thistles. Vassar Quarterly, 38-42 4. Sugar Ph.D., M.D., O. (1992). Dorcas Hager Padget: Artist and Embryologist. Surgical Neurology, 38, 464-8 |