FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

ICE AGE BEASTS BEGET MODERN LESSONS.

YOUNG HERDER GUNNAR TAMES THE MUSK OX.

read the essay now >>

|

To break into the world of musk ox husbandry, one needs little more than willingness and luck. While becoming a truly professional cattleman can take a lifetime, musk ox herders rise to the specialist level quickly. This is due to an extreme lack of human knowledge of, or experience specific to this ice age animal. President Theodore Roosevelt once said that "the best prize life has to offer is a chance to work hard at work worth doing." When I look back at my work on a musk ox ranch in rural Alaska, I find myself still waiting for the judges’ decision on this award. But this job has at least afforded me rare insight into what is arguably the oldest and most pivotal work in man’s history: domesticating animals. Philosophy majors are in no I do not boast to possess any unique skill in working with these animals, or in operating a sustainable agricultural non-profit organization. My vocation simply unfolded as a matter of necessity, born from my own personal economic needs: Philosophy majors are in no higher demand today than they were at the time of Socrates' trial.higher demand today than they were at the time of Socrates' trial. |

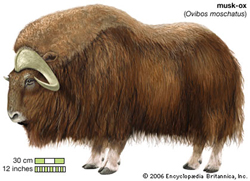

"Herder of musk oxen" on a resume does little to qualify you for much in the "lower 48" (as we Alaskans refer to the rest of the United States). But up North, it makes you privy to an exclusive club whose membership is limited to only a handful of people in the world. Musk oxen will pursue a dog In this business, scraps of knowledge translate into gold: musk oxen do not kick; musk oxen will pursue a dog in murderous rampage, because of their resemblance to the musk oxen’s natural adversary: the wolf. To then acquire tangible experience to back this knowledge soon makes you more rarely qualified than the best of Spanish matadors.in murderous rampage. Musk ox husbandry cannot be discussed without considering the idea of domestication: a very pesky word that defies clear definition, and to which National Geographic recently dedicated an issue. On one hand, domestication is a matter of biology. Floppy ears, piebald colorations and curly tails are all traits found only in the domesticated realm of the animal kingdom—if for reasons that elude those who study the subject. |

|

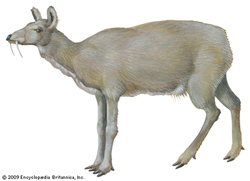

On the other hand, the same term signifies something more vague when one compares a tamed wolf to a feral dog. On the physiological level, when we say that an animal has been "domesticated," it means that its first impression of man does not elicit fear as it would in its wild counterpart. Of course, the fear of man so strongly innate in many wild animals can be stomped out to varying degrees, but will reemerge with every subsequent generation. One fateful day, the first wolf pup was born with floppy ears, forever altering the trajectory of mankind. Musk oxen are still far from that day, as we have only ventured a mere fifty years into an arguably five hundred-year-long process. Musk ox. If your mind conjures up an image of a smelly, black, cow-looking animal with a bullring through its nose—yoked to a plough somewhere north—I don’t blame you. This is what the misnomer musk ox would imply. The term was coined by the first Europeans to stumble across musk oxen, in order to associate their discovery with a commodity; the perfume fixative derived from the musk gland of deer from the Moschiadae family. In the 19th century, such musk (which musk oxen do not have) was a highly-sought good on European markets. |

The “musk” these Europeans ascribed to musk oxen was most likely just the pungent scent that bulls emit during their rut in late summer. And the choice of “ox,” if I was to guess, could have just as easily been “buffalo,” “bull,” or any other such term for the bovine ungulates that scattered our planet at the time. Much in the way that bison incorrectly became “buffalo,” “oxen” was chosen due to a lack of imagination on the part of foreigners who were likely blinded by thoughts of trade value when they first looked upon these leftover remnants of the last ice age. In the 19th century, such musk was a highly-sought good on European markets. Eskimos refer to the musk ox—thought by these early arctic explorers to be the most dangerous animal in the world—as oomingmak, meaning simply, "the bearded one." This name more aptly fits with the mission of the organization which employees me. The bearded ones, while lacking the commodity of musk, do possess a commodity within their beards precious enough to drive our work.Initially, the most notable feature of the musk ox is its massive horn boss, which can exceed six inches in thickness, and serves as a main form of defense. This horn boss is the centerpiece |

|

of the ritual that musk oxen perform to determine the hierarchy of the herd. Nonetheless, the truly defining characteristic of the ox is its underwool, or qiviut (pronounced “ki-vee-oot”). Qiviut keeps these animals warm at negative 60 degrees Fahrenheit on the arctic tundra, when there is nothing to subsist upon other than the sparing lichens found several feet under the snow. Their qiviut beards have allowed the musk oxen to survive for several millennia where few other species have managed. Our herding these thousand-pound animals is all done for the sake of obtaining the fiber they molt every spring. It is the fiber in qiviut that has led a host of foolhardy people since 1954—in whose ranks I must now be counted—to venture to domesticate these arctic survivors. Our particular ruminates appear as though they should be fending off saber-toothed tigers, or walking next to wooly mammoths (whose wool was likely nearly the same as the musk oxen’s qiviut; a recent mammoth exhibit on display at the Anchorage Historical Fine Arts museum used qiviut to explicate this very point). It is odd to think that our herding these thousand-pound animals and climbing into small stalls with them is all done for the sake of obtaining the fiber they molt every spring. |

He was interested in creating a sustainable form of northern agriculture to benefit the peoples of the rural arctic. The founder of the entire project to domesticate musk oxen was an anthropologist named John Teal; a Harvard man who taught at Dartmouth and the University of Fairbanks, among other notable institutions. He was interested creating a sustainable form of northern agriculture to benefit the peoples of the rural arctic. It was this very human perspective that inspired Teal’s idea to catapult these arctic peoples from a hunter-gather society, into the next stage of anthropological development; an agrarian society. Musk oxen—or, more precisely, their qiviut—just happened to be the means through which this very human end might be reached. Thus, musk ox husbandry was born. Teal’s ingenious vision is a prelude to the twenty-first century’s infatuation with anything to which the word "sustainable" can be attached. Something passionate must have existed in Teal for him to have the gumption and fortitude to arrange an expedition into the arctic to capture some thirty-odd calves from wild herds of musk oxen. |

|

Having personally been charged (pun intended) with the task of collecting many calves from their mothers (who can run at speeds of up to 35 miles per hour) for vaccination, I can assure you that such capture is an intimidating prospect. And I am at least armed with a tested method, along with the knowledge that such a task is possible. Teal’s initial capture necessitated not only a profound understanding of the physiology of these animals, but that spirit of adventure that equally defines American candor, and harks back to Homer’s Odysseus. Like the other oldest professions, its name has always rung with an unsettling and inherently exploitative quality. Nonetheless, domesticating animals is perhaps among the oldest of professions and, like the other oldest professions, its name has always rung with an unsettling and inherently exploitative quality. This is particularly true when domestication was combined with the rampant idealism of the American 1950s, and then performed with an unprecedented and artificial imposition of structure and scientific rigor. |

The process of domestication was forged over thousands of years; the natural result of a coincidence between necessity and convenience. Teal’s project, though driven by very noble aspirations, has made a very strange alliance between the classic American pastime of taming the West, and the most outlandish and brash forms of Anglo-American efforts to embrace the true peoples of North America, so brutally repressed by said westward expansion. In this respect, the project stands as a bizarre blend of cultures normally at odds with one another. As we administer the non-profit corporation that ensued from Teal’s vision, quviut from our farming efforts is supplied to rural Alaskans. This supply provides them with a semi-local economic means to subsist in the bush that does not disrupt their ancestral lifestyle. Yet the very antithesis of such ancestral ways are employed through the cold, institutional human control we adminster to tame a wild animal. Circularly, this is all to ensure that the original culture, accustomed to coexisting with said wild animal, can be incongruously sheltered from the onslaught of human oil money and pork barrel politics. |

|

In 1928, Dorothy Parker noted that “work is the province of cattle.” My experience has been quite the converse. Working with musk oxen in the context of a non-profit setting has led me to an analogy: though the two vocations would seem to be antitheses, they share a common motion. The herder must convince the entity in front of him that what he stands for is a force to be reckoned with, regardless of whether or not this reflects the truth. When running at a bull that outweighs you by roughly five times, you must firmly convince yourself of your own feeble clout—and project this impression so convincingly that the bull is left with no doubts in his mind, either. Driving forward the mission of a non-profit carries a similar sensation. Do it enough times, and truth emerges from the noble lie. When running at a bull that outweighs you by roughly five times, a herder must firmly convince himself of his own feeble clout. My day-to-day ox herding activities are interspersed with carrying out the nonprofit’s mission. This includes dispersing daily rations of grain and hay, repairing vehicles with duct tape and welding massive pieces of livestock equipment out of unwanted railroad track. It also includes |

One must add to these tasks the uniquely Alaskan allure of hardship and ruggedness. writing grants, giving tours to visiting diplomats and organizing research to further fulfill the original mission of Teal. One must add to these tasks the uniquely Alaskan allure of hardship and ruggedness. Leaving modesty aside, I can’t help but boast that my work is frequently performed in seventy-five-mile-per-hour winds at –20 degrees Fahrenheit. We heat the single-room cabin that serves as our corporate headquarters with a wood-burning stove.My work is frequently performed in seventy-five-mile-per-hour winds at -20 degrees Fahrenheit. Walking away from this project at the end of the day, my final judgment ultimately rates the non-profit’s potential to survive as even more difficult to ensure than that of our captive oxen. This begs the question: Should such an imposition of structure on an otherwise natural process—namely, domestication, which can take in excess of 500 years—be undertaken at all? To return to my axiom, it has not yet become clear to me whether I’ve found life’s prize somewhere out in the |

|

pastures, or nestled within a sheet of qiviut. But perhaps I need hindsight before making such judgments. While the telos of the ox lies in its resource, my time among the oxen will forever be defined by moments at two in the morning with the wind howling, the moon lighting the snowy farm ablaze, walking through the drowsy herd huddled in their beds of snow. They do recognize me, and not as a stranger who walks through the pasture, though still not as one of their own. They look up and then rest their heads down again. If I pause, or look too long, they jump up—ready to begin, once again, the long walk on the boundary between wild and domestic. But if I read them subtly, they remain at rest. I walk away leaving the pastures undisturbed, as though I had left no prints in the snow to show where I had tread.  |

Notes: "Theodore Roosevelt." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011. Web. 07 Sep. 2011. "Socrates." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011. Web. 08 Sep. 2011. "musk deer." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011. Web. 07 Sep. 2011. "musk." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011. Web. 07 Sep. 2011. Eskimos: Alaska Native Language Center, Kaplan, Lawrence; Inuit or Eskimo: Which name to use?; http://www.uaf.edu/anlc/resources/inuit-eskimo, accessed 9-8-11 |

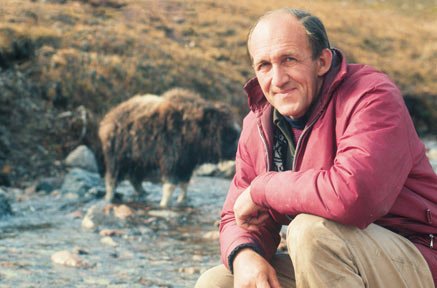

John Teal Jr. (1923-1984), founder of Oomingmak, the Musk Ox Producer's Cooperative, was born in New York City and graduated with a degree in anthropology from Harvard University. He later received a masters in International Relations from Yale University. In 1953, Teal founded the Institute of Northern Agricultural Research (INAR) in an effort to improve the economic and social condition of the native arctic people by cultivating indigenous plants and capturing animals for domestication. When the project began, the musk ox was on the verge of being decimated, and the villages along the coast of Alaska were considered some of the most impoverished places in the world. The Oomingmak Knitters Coop is supplied by the Musk Ox project and has created a cottage-based textile industry. The driving philosophy behind the project was to develop a gentle agriculture based on the perennial harvest of the Musk Ox's fine underwool, quiviut, in order to create a fiber-based economic activity in arctic villages. This approach was ahead of its time: Teal was an early proponent of what is now widely known as sustainable agriculture. For more information on the current state of the project, visit the Musk Ox Farm's web site, www.muskoxfarm.org.

Photo of John Teal Jr.

http://www.muskoxfarm.org/history

Coda

There's little in taking or giving,

There's little in water or wine;

This living, this living, this living

Was never a project of mine.

Oh, hard is the struggle, and sparse is

The gain of the one at the top,

For art is a form of catharsis,

And love is a permanent flop,

And work is the province of cattle,

And rest's for a clam in a shell,

So I'm thinking of throwing the battle ---

Would you kindly direct me to hell?

The Complete Poems of Dorothy Parker, Penguin Books, 1999.