FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

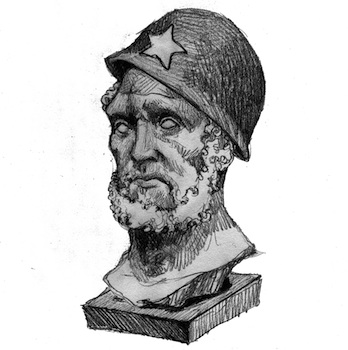

MILITARY VALUES HAVE ANCIENT ORIGINS.

RAJIV REVIEWS THREE VIRTUES, PAST & PRESENT.

Read the essay now >>

|

Military culture has accommodated many dramatic shifts in order to evolve from aggressive phalanxes, to the “hearts & minds” development projects of Iraq’s factionalized urban landscape. But in the halls and classrooms of America’s greatest military institutions, value-based principles of war remain immutable. Though tactics and strategies change, “duty, honor and country” form a timeless trinity, reiterated in order to direct conduct and character. Though tactics and strategies change, As a West Point graduate and combat veteran, I have carried such classical military values with me. And yet, on battlefields of Afghanistan and Iraq today, these values sometimes diverge from classical expectations of virtue. Interpretation of these ideals also shifts, depending on whether you are a combat leader in the moment of battle, or a member of the public issuing judgments after-the-fact."duty, honor and country" form a timeless trinity. Can we truly claim that the same ethos that motivates the soldier under modern American body armor motivated the shield-wielding warrior at Marathon? It is impossible to see inside the heart of every soldier, whether modern or ancient. But by examining received doctrine and societal reaction, |

we can loosely study the prevalence and consistency of certain military values. The motto of the United States Military Academy at West Point is Duty, Honor and Country. While these staple values move modern military formations, past conflicts show that the concept of “country” was not always consistent for all combatants. For example, countless insurgents the world over have fought, not necessarily for the sake of an established government, but against an oppressive one. Thus, I will substitute the value of “Country” with that of “Loyalty.” I see loyalty to a cause, unit, country or people as a major motivator behind split-second decisions made on the battlefield. In my contemporary interpretation, these terms mean: Duty: Something that one is expected or required to do by moral or legal obligation Honor: Honesty, fairness or integrity in one’s beliefs and actions Loyalty: Being faithful to one’s oath, commitments or obligations |

|

I want to examine two cases, past and present, that speak to the most common and prolific application of these three values (as opposed to their utility in intense conflict). VALUE JUDGMENTS "The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must." --Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War Ancient Greek general Miltiades the Younger (c. 554-489 BC) used lightning-quick judgment to persuade the other nine generals of the Athenian land forces to strategically exploit a weakness in the Persian cavalry. He thus led his men to decisive victory at the Battle of Marathon (490 BC). Soon after becoming a war hero, he pursued war in the Athenian colony on the Thracian Chersonese (originally founded by his step-uncle). While Miltiades the Elder had done his best to promote a defensive strategy to protect the colony from hostile natives, the latter Miltiades chose a more aggressive stance. His tactics included the brutal killings and imprisonment of the natives on present-day Gallipoli. In 489 AD, he led an Athenian expedition of ships against a series of Greek islands assumed to have Persian affiliation. His rampage on the Aegean island of Páros was nothing more than a “noble” showing of forces, during which |

he incurred a probably fatal leg wound. The Persians retained the island. Because of his failed attempt at Páros, Miltiades was not received in his Greek home of Athens with open arms. Instead, this former hero was ostracized by his own countrymen for his inability to withstand his enemies in battle. His political rivals exploited this weakness and ousted him from power. He was charged with treason and sentenced to death. His sentence was later reverted to time in prison, where he soon died. He was charged with treason What captivates me about this case study is not simply the brutal tactics or aggressive behavior of Miltiades. His society’s demand for perfection in his brutal duties of loyalty suggests a culture that valued ends over means. What, can we speculate, were the values motivating Miltiades before and after Marathon? And which spoken or unspoken cultural values did he fail to live up to, so as to anger his country so deeply that they sent him to prison for life?and sentenced to death. For Miltiades, we could argue that his thirst for glory was rooted in a sense of loyalty to his ethnicity and home colony. His sheer hatred against |

|

the natives of his Thracian colony could be explained by his step-uncle’s struggles to protect the islands during his own tenure. His brutal tactics could simply be viewed as acceptable means towards a desired end of fulfilling a loyal mission towards his father and his country. Is this analysis perhaps shortsighted and imprudent? Absolutely, but that does not change the value of use; more importantly, it simply allows us to understand that “loyalty” in ancient warfare had alternative interpretations than in today’s military. When Miltiades’ country felt a sense of trust and loyalty towards their leader, it was likely expected that the primary objective of his leadership was the fulfillment of his obligation to protect (and to prudently expend resources in doing so). Thus, for the people of Athens, the value that Miltiades perhaps most seemed to undermine with his brutal excesses was that of duty. On the other hand, in what pre-democratic Greek nation-state was it remotely acceptable for a leader—whose exceptional performance included his sacrificing a leg in battle—to be so strongly hated and ostracized? The value of “duty” held strongly with the people of this colony. Its perceived violation was not about sheer spirit in fighting, nor about great victories, but rather an ultimate evaluation of Miltiades’ total success (or, in this case, failure). |

Let us now fast-forward to a modern day example of warfare with hugely lesser degrees of violence, but a much larger scope of secondary and tertiary effects. The threats became more ominous and likely. A battalion commander in today’s army leaves the responsibility for combat interrogation to those trained in effective methods, and the legal rights of detainees. While serving in Taji, Iraq, LTC Allen West received information from an intelligence specialist about a reported plot to attack his unit in an upcoming mission. An Iraqi police officer was supposedly involved. The threats became more ominous and likely.On a completely separate mission a couple weeks after the notification of the threat, but before the actual execution date, a mission left from West’s forward operating base—a mission that, according to CNN and other sources, West was supposed to join. The convoy was ambushed. West had never conducted or witnessed an interrogation, but had his men detain Officer Yaha Hamoodi, an Iraqi police officer. In the process of detaining Mr. Hamoodi, soldiers testified that Mr. Hamoodi appeared to gesture towards his weapon, |

|

so the men claimed that he had needed to be subdued. Hamoodi was beaten by four of West’s soldiers from the 220th Field Artillery Battalion on the head and body. The battalion commander proceeded to conduct his own personal investigation of the Iraqi police officer. In an attempt to intimidate him, he drew his pistol and fired a bullet near Hamoodi’s head. In an attempt to intimidate him, he drew his pistol and fired a bullet near Hamoodi's head. Hamoodi cracked. He disclosed names–what Hamoodi later described, according to a May 2004 New York Times report, as "meaningless information induced by fear and pain." At least one suspect was arrested as a result, but no plans for attacks or weapons were found. West said, "At the time I had to base my decision on the intelligence I received. It's possible that I was wrong about Mr. Hamoodi."West was charged with violating articles 128 (assault) and 134 (general article) of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). During a hearing held as part of an Article 32 Investigation in November 2003, West stated, "I know the method I used was not right, but I wanted to take care of my soldiers." The charges were ultimately referred to an Article 15 proceeding rather than a court-martial, at which West was fined $5,000. LTC West |

accepted the judgment, and retired with full benefits in the summer of 2004. The information here is again pertinent to context. Some of the values that this officer held so true to his own heart were likely similar to those that once motivated Miltiades. LTC West had a fierce sense of loyalty to his men; so much so that he would rather violate international law than risk their lives. The lives of nearly a thousand soldiers rested on his shoulders, and numerous casualties had already meant penning For the average citizen, the notion of military loyalty may go over cold, but we must be frank and fair to LTC West’s position. As a battalion commander, you are the senior battle space owner for a defined area of operations where everything that happens—and doesn’t happen—is the battalion commander’s responsibility. The lives of nearly a thousand soldiers rested on West’s shoulders, and numerous casualties had already meant penning letters home to parents and wives.letters home to parents and wives. Having served as a platoon leader in Afghanistan, it is easy for me to understand why there were no means spared by LTC West to keep his men safe. |

|

His fierce loyalty trumped other values of leadership. But the secondary and tertiary effects of the incident resonated throughout the Taji district, and the area became far more violent after West’s relief of command. What began as a UCMJ violation meriting a court-martial ended as a $5,000 fine for the battalion commander. The degree of compassion here showed by the military toward this leader—who arguably condoned torture, and potentially could have set the counterinsurgency movement in Iraq back by a decade—is outstanding. But the compassion shown by the courts and country in this case was not necessarily a form of “loyalty.” Rather, I consider this result more a factor of “honor” than of loyalty or duty. Does a civilian society have the authority to judge its warriors for their actions in combat? Less than half a percent of LTC West’s country serves in uniform; and even fewer take hostile fire from the enemy. In a counterinsurgency conflict, archaic or academic rules of war sometimes seem alien when imposed upon those with the fire of adrenaline and fear running through their veins. Does a civilian society have the authority to judge its warriors for their actions in combat? Did the Athenian people have grounds upon which they could reasonably expect more from their commander, Miltiades, when many |

could not empathize with his leadership dilemmas? These debates quickly become not a matter of duty codes, but of simple honor. Honor can also include a society admitting honestly that our outside judgment can be fallible in some cases, even if we generally agree that the actions of men in war should be governed by stable moral principles. Duty, honor, transgression: The juxtapositions here show that adherence to one classical value may ultimately conflict with another. To me, the LTC West dilemma implies a more intricate moral weaving than the unquestioned certainty we often romanticize as characteristic of classical military leaders. Bedrock principles are problematic in that their interpretations are various, and change with context or hierarchy. With new technology come new skills, new training... and new culture. New forms of discipline are required to guide those mastering the craft of warfare. The values themselves—or at least the words we use—have not changed. Duty, Honor and Loyalty are still staple values that guide me, and all of us in the military community. As a soldier who recently emerged from the moment of battle, I hope to reinforce civilian empathy for the demands of value-based leadership, reiterating the nuances of these classic values in the public sphere.  |

Rajiv later connects the warrior's honor culture of the classical world to modern military honor codes. But it is important to note the slow historic shift from ancient Greek honor culture, through Roman virtus and pietas, on through the comparitively progressive Christian values of otherworldly, pacifist distinction (and in the ideal of the "Christian soldier," an ongoing tension of such virtue with knightly or aristocratic concepts of honor).

Journalist, editor and scholar James Bowman traces this distinction in his Honor: A History (2006), where he notes that 20th century classicist "Werner Jaeger remark[ed] that 'Homer and the aristocracy of his time believed that the denial of honour due was the greatest of human tragedies. The heroes treat one another with constant respect, since their whole social system depends on such respect. They have all an insatiable thirst for honour, a thirst which is itself a moral quality of individual heroes.' But honor is to them, as to Greek philosophers in rationalizing it, emphatically public...[thus setting] the Greeks apart from more strictly functional honor cultures that ruthlessly subordinated the individual to the larger society."