FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

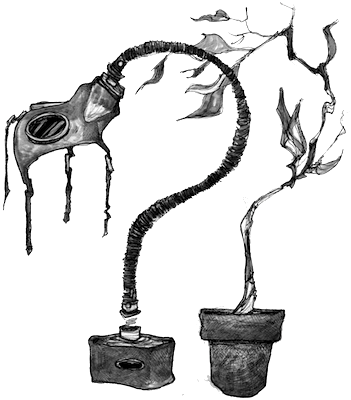

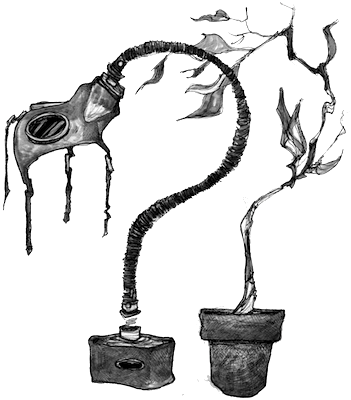

NUCLEAR ATROPHY

NUCLEAR ATROPHY

ACCIDENTS CHOKED NUCLEAR PROGRESS.

NUCLEAR ENGINEER MARK SEEKS RENEWED TRUST.

Read the essay now >>

ACCIDENTS CHOKED NUCLEAR PROGRESS.

NUCLEAR ENGINEER MARK SEEKS RENEWED TRUST.

Read the essay now >>

|

During the 1970s, nuclear energy in the United States had achieved its acme. Over one hundred reactors were either operating or under construction. Nearly all of these were light water reactors—either pressurized water reactors (PWRs) or boiling water reactors (BWRs)—loosely modeled after Admiral Rickover’s original innovation. Concurrent to, or rather countercurrent to, this rise of nuclear energy was the rise of its public opposition. The modern environmentalist movement blossomed with a chief aim to oppose nuclear energy based on a perceived lack of reactor safety and the potential for radiation health risks. Consumer activist Ralph Nader was the titular head of the U.S. anti-nuclear movement, and he garnered national attention for his efforts. Hollywood didn’t wait long to create a politically charged thriller on the issue, releasing The China Syndrome in 1979. “China syndrome” is jargon for a fictional severe nuclear reactor accident in which the entire core melts through the reactor vessel and into the earth’s crust, even “all the way to China.” Although it is possible (albeit extremely unlikely) for a reactor core to melt through its vessel and containment, such a global scenario is preposterous. In the film, a news reporter (Jane Fonda) and her cameraman (Michael Douglas) inadvertently discover that a fictional reactor is actually unsafe, and that its construction company falsified regulatory documents.The cameraman |

Mark Reed speaks about testing materials in a light water reactor in Part IV of Fortnight's tour. attempts to uncover this fact, but company goons attempt to silence him in an absurdly dramatic chase that culminates in a SWAT team shooting. In the film, a physicist posits that a real China syndrome event could render “an area the size of Pennsylvania” uninhabitable. The China Syndrome debuted on March 16th, 1979. Twelve days later, on March 28th, the worst nuclear accident in U.S. history occurred in central Pennsylvania. The Three Mile Island (TMI) Nuclear Generating Station is situated on the Susquehanna River, just south of Harrisburg. The site has two separate light water reactors, TMI-1 and TMI-2. In the early morning of the 28th, an emergency valve TMI-2 |

|

|

became stuck open. These valves are intended to open for a brief period of time in order to release a small amount of water coolant during situations in which the pressure becomes too high. However, this particular valve malfunctioned such that it remained open long after it should have closed again, releasing too much coolant. This is what nuclear engineers refer to as a “loss of coolant accident”. When too much coolant is lost, the reactor core is not fully cooled—it heats up, and, if the process isn’t stopped, it eventually begins to melt. Tragically, due to confusion regarding certain system indicator lights in the control room, the operators at TMI did not realize that the value was stuck open. Coolant was accidentally lost, and the core had already begun to melt. Ultimately, about half of it melted. This was not nearly enough for “China syndrome” to occur, though; the core remained in its vessel. But this incident was not without serious consequence. When a loss of coolant accident releases heated water, that water usually flashes into steam as soon as it escapes its pressurized piping. During the TMI accident, the concrete containment structure enclosing the reactor was filled with this steam until its pressure became unacceptably high. In order to counter this phenomenon, operators intentionally vented some |

of this steam directly into the atmosphere. Since this steam originated from water in contact with the melted core, it contained small concentrations of radioactive material. Thus, the TMI accident included a small intentional release of radiation into the atmosphere. The aftermath of the TMI accident was relatively benign in terms of engineering and health. The TMI-2 core was removed, and the remainder of the reactor remains at the site. TMI-1, which was not damaged in the accident, continued operation in 1985 and continues to produce electricity today. No one was killed or seriously injured in the accident, and the radiation release was far too small to cause any substantial health risk to the public. Despite this, political reaction was severe. The untimely release of The China Syndrome, one of Hollywood’s most famed coincidences, sensationalized nuclear accidents and greatly exacerbated public reaction to the TMI accident. Six months later, The China Syndrome’s leading lady Jane Fonda held an anti-nuclear rally with Ralph Nader in New York City that attracted about 200,000 people.1 Catchphrases such as “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) became commonplace, with the pro-nuclear satirical retort being “build absolutely nothing anywhere near anything” (BANANA). |

|

Public support for nuclear energy dropped off to well below 50%. The ultimate result was that no new reactors were constructed in the U.S. for thirty years. *** I was born and raised in the Pacific Northwest, near Seattle. My father was a chief engineer in the Merchant Marines, and Seattle was his most oft-visited port. After he retired, my parents moved over the Cascade Mountains to the eastern portion of the state, which is starkly different in terms of geography and culture. It’s bucolic and beautiful—sprawling farmland, arid hills, and deep river gorges. It’s also home to the Hanford Site, where the world’s first large-scale reactors were covertly constructed for the Manhattan Project.When I was fourteen, my eighth grade class split into several groups, each spending a week touring a different region of the state. My life-long friend Stephen and I were placed in “The Gorge Group.” We were to travel along the Columbia River Gorge, which cuts an east-west trough through the Cascades on the Washington-Oregon border. Stephen’s father was a mechanical engineer who had done some consulting work for the Hanford Site, which is about two hundred miles upstream |

from the gorge. He strictly forbade Stephen to swim in the river. Although it’s true that the early Hanford reactors released significant quantities of nuclear waste into the Columbia River during the 1940’s, the current health risk due to radiation in that river is vanishingly small. The water was gorgeous, and it sure would have felt great on one of those hot summer days. *** Seven years after the TMI incident, the Cold War foes of the United States suffered a more severe embarrassment.While most western nations championed light water reactors, the Soviet Union chose a different route. They built numerous High Power Channel-type Reactors (abbreviated RMBK in Russian), which are cooled by channels of light water but also include substantial masses of graphite to aid in slowing neutrons. The RBMK is advantageous in that in requires no isotopic enrichment—it can be constructed using only natural compositions of fuel, water and graphite. However, this combination of light water and graphite is highly unstable in that loss of the water |

|

coolant will cause the rate of fission in the core to rise rapidly. Although loss of coolant in any reactor will cause the core to overheat, loss of coolant in unstable reactors will cause this (more dangerous) rapid rise in the fission rate. One Soviet RBMK, the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant near the Ukraine-Belarus border, was especially unstable in this way. Furthermore, its reactor control system design contained an exceptionally foolish flaw. On April 26th, 1986, the Chernobyl RBMK core blew up. While the TMI accident was primarily an operational error, this was primarily a (much less excusable) design error. The foolishly flawed control system caused an initial spike in the fission rate, which the RBMK’s inherent instability amplified through rapid positive feedback. This was not a nuclear explosion. It was a thermal, mechanical and chemical explosion. Essentially, the whole reactor exploded. This was not a nuclear explosion— it was a thermal, mechanical and chemical explosion. Even the most ill conceived reactors could never explode as nuclear weapons do. However, the explosion was severe enough to scatter bits and pieces of the core across a vast swathe of the Ukrainian-Belarusian |

countryside. A radioactive cloud of gaseous fission products (most notably cesium and iodine) gradually spread out over most of Europe. This cloud was too thinly concentrated to cause immediate harm to anyone beyond the Soviet Union. Most of the plant crew died of radiation sickness within a few weeks, and the death toll eventually reached over two hundred. To this day, a nineteen -mile radius “exclusion zone” surrounds the Chernobyl site. No one may live there due to radioactive contamination. The tragedy at Chernobyl was unquestionably the world’s worst nuclear disaster. It was also a harbinger of the Soviet Union’s impending collapse; an indicator that their former engineering prowess had dwindled to the point that such an embarrassing (and entirely avoidable) disaster could occur. At first, the Soviets attempted to conceal the disaster. In fact, Western Europe knew nothing of it until Swedish facilities detected the radiation release two days later. However, once the truth was out, the political reaction in Europe was no less severe than that in the U.S. following the TMI accident. The Netherlands held their national election in May of 1986, less than a month after the disaster. The Dutch |

|

people, who had previously considered nuclear energy as a viable option, quickly abandoned it.2

*** During the 1980s, as a result of the TMI and Chernobyl accidents, public opinion in the U.S. and most of Europe swung heavily against nuclear energy. Global nuclear energy installation stagnated. People are myopic by nature—they tend to lose sight of important long-term goals in favor of whatever peril seems to loom large at the moment.France was the exception. From 1980 to 2000, the French went from about 25% nuclear energy to about 80% nuclear energy. Chernobyl didn’t thwart their energy policy. Instead, pro-nuclear activists glorified nuclear technology. French author Jacques Leclercq elegantly eulogized nuclear energy when he wrote:

The age in which we live has, for the public, been marked by the nuclear engineer and the gigantic edifices he has created. For builders and visitors alike, nuclear power plants will be considered the cathedrals of the twentieth century. Their syncretism mingles the conscious and the unconscious, religious fulfillment and industrial achievement, the limitations of uses of materials and boundless artistic inspiration, utopia come true and the continued search for harmony.3

|

Why did France buck the international trend? It’s complicated, but the short answer is simply that people wrote beautiful things about nuclear energy. The truth is that nuclear energy, as Bill Gates once said it, incurs fewer “deaths per kilowatt hour” than many other electricity sources, especially coal.4 The TMI accident, though fairly severe, didn’t actually harm a single person. The Chernobyl disaster, although tragic and deadly, was more indicative of the Soviet Union’s decline than anything about nuclear energy in general. Unfortunately, facts and reasoning don’t move people. Instead, images move people. Beauty moves people. Ugliness moves people. In the U.S., ugly Hollywood-esque memes related to radioactive contamination and nuclear industry conspiracies moved people to oppose nuclear energy. In France, beautiful acclamation moved people to support nuclear energy. As a nuclear engineer, I recognize that my chosen field is a political issue, inextricably tied to the whims and vicissitudes of public opinion. We nuclear engineers don’t just have engineering challenges. We also have public image challenges. We can have the best ideas and perform the best work, but if we neglect our public image, everything we do is in vain. We can design the |

|

most innovative reactors for a clean energy future, but if we don’t have public support, we will never realize that future. That’s why I’ve chosen to write for Fortnight Journal: to humanize the nuclear engineer and expose the beauty of nuclear technology.  *** Mark Reed received his S.B. degree in Physics, as well as his S.B. and S.M. degrees in Nuclear Science and Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Nuclear Science and Engineering. To view his previous pieces in Fortnight—including an exclusive video tour of the MIT Nuclear Reactor—see Violent Nascence, From War to Peace and Nuclear Waste & Medicine. |

SOURCES

1. Herman, Robin (September 24, 1979). "Nearly 200,000 Rally to Protest Nuclear Energy". New York Times: p. B1. 2. Affect of Chernobyl on 1986 Dutch General Election: doc.utwente.nl/60945/1/visser1994pol.psych.art.94.pdf 3. The Nuclear Age by Jacques Leclercq: http://books.google.com/books/about/The_nuclear_age.html?id=pOSAQgAACAAJ 4. Bill Gates on nuclear safety: http://techcrunch.com/2011/05/03/bill-gates-nuclear/ |