FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

GENERATIONAL DISASTERS

GENERATIONAL DISASTERS

MILLENNIALS REMEMBER DISASTER WITH TECH.

CARTOGRAPHER VICTORIA MAPS OUR

FIRST THREE NAIL-BITERS.

Read the essay now >>

MILLENNIALS REMEMBER DISASTER WITH TECH.

CARTOGRAPHER VICTORIA MAPS OUR

FIRST THREE NAIL-BITERS.

Read the essay now >>

|

Facebook lists my favorite television show as The Weather Channel’s “Local on the 8s.” It is not a joke. Both cartography and the physical geography of weather patterns are covered by the wide umbrella of geographic studies. If I had followed a slightly different track a few years ago, I just as easily could have written these essays about the Doppler Effect, or how hurricanes are named. Our generation came of age at the same time as the Weather Channel, Our generation came of age at the same time as the Weather Channel, which started broadcasting in 1982. We observed blizzards, hurricanes, tornadoes and all kinds of natural disasters with the benefit of the best modern technology. We saw hurricanes forming way out in the ocean through satellite imagery and high-tech radar displays. We knew in advance that we could stay up late, because TV showed us that a storm would blanket our towns with snow overnight.which started broadcasting in 1982. As a tribute, I submit maps and analysis of three natural disasters especially memorable to the millennial generation. |

1991: The Eruption of Mount Pinatubo Mount Pinatubo is located on the southwestern side of Luzon, the largest island of The Philippines. Up until the late 20th century, Pinatubo was just another mountain in the Zambales range, none of which were thought to be active. The last eruption had occurred 500 years prior. Luzon, however, is close to the Manila Trench, the subduction zone where the Eurasian Plate forces itself below a complex group of microplates known as the Philippine Mobile Belt. As the PMB is one of the most seismically active locations on the Ring of Fire, it was probably only a matter of time. |

|

Mount Pinatubo’s eruption was a months-long global event, escalating from a springtime series of small seismic actions to the remarkable June 1991 eruption. But the story really began on July 16th, 1990, when the strongest earthquake of that year tore through Luzon with a devastating 7.8 magnitude. It was centered 100km away from Pinatubo itself, but those close by reported steam rising from the slopes. Smaller quakes continued throughout the winter. Those close by reported steam By March 1991, a series of smaller, closer quakes literally shook those same residents into the knowledge that Mount Pinatubo wasn’t dormant any longer. For two weeks, increasingly dire earthquakes rocked the countryside as magma pulsed under the surface. On April 2nd, 1000+°F magma made contact with water, and the instantaneous evaporation caused a massive explosion. This type of eruption, a phreatic eruption, was how Krakatoa (Indonesia, 1883) and Mt. St. Helens (Washington State, 1980) went up. But for Pinatubo, it was just another blip on the timeline.rising from the slopes. April 26: the US military sets up monitoring stations at Clark Air Base, fifteen miles east of the |

summit. May 16: fissures near the summit released sulfur dioxide gas. June 1: multiple earthquakes were recorded with an epicenter 5 kilometers directly beneath the mountain. June 5: the summit bulged upward and outward, thick with magma. June 10: 14,000 were evacuated from Clark Air Base. June 12: an ash column twelve miles high grew over the volcano. Near-constant shallow earthquakes, tephra and pyroclastic flows marked the next two days. An ash column twelve miles high All of this was nothing compared to June 15: Cauliflower-shaped ash clouds rose 20 miles into the air, darkening much of the island. Over nine hours, the volcano spewed gas, ash and other earthen materials into the air and onto the landscape. With horrible timing, Typhoon Yunya passed 45 miles north, adding rain to the already rapid lahars.grew over the volcano. It was the second-largest eruption of the twentieth century. The largest was Novarupta, on the Alaskan Peninsula in 1912—which was far less destructive overall, given that the nearest city, Anchorage, was 300 miles away and not yet fully settled. |

|

1993: The Superstorm (a.k.a., the Storm of the Century) This is the one event on our list with which I have direct personal experience. I was seven when the Superstorm hit. It was a few days before my eighth birthday, in fact. Now, in suburban Buffalo, ten to twelve inches of snowfall would be a little higher than average but not unusual. After all, when you think of March in Buffalo, you think, “snow.” But in early 1993, our cousins in Atlanta reported the same amount. |

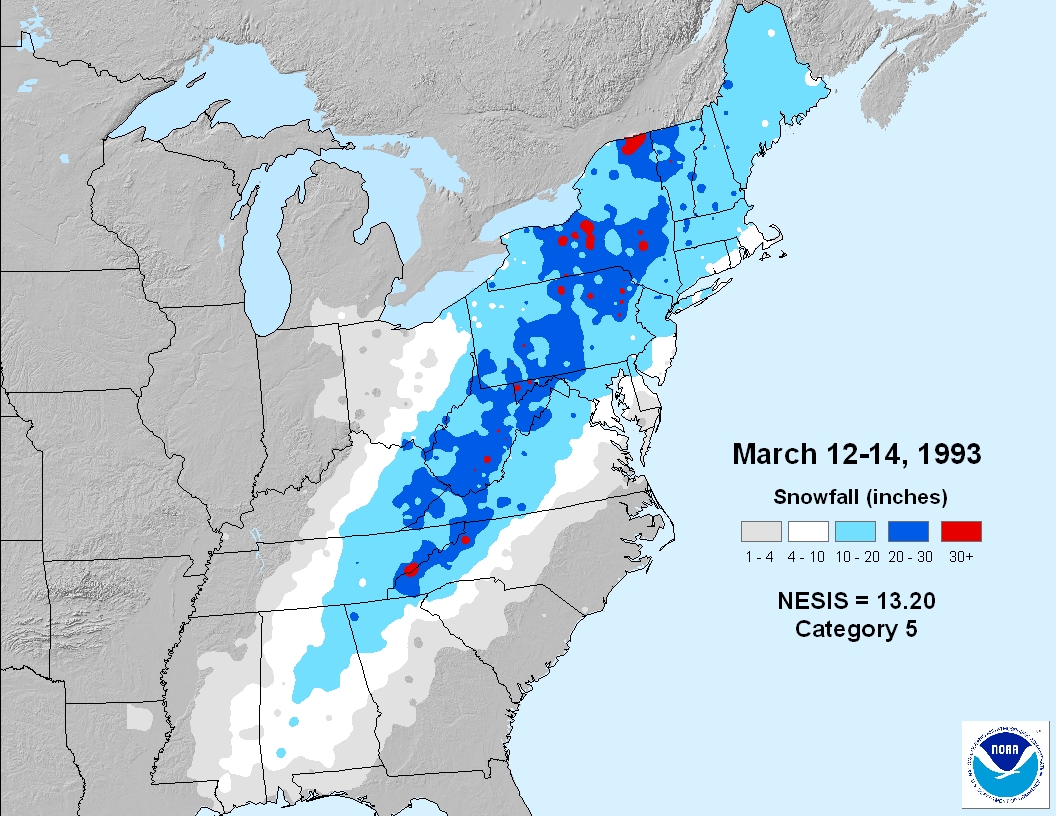

NOAA’s Northeast Snowfall Impact Scale has five levels: Notable, Significant, Major, Crippling, and Extreme. Since the 1950s, there have been only two storms worthy of the label “Extreme.” This was the first: A single storm, stretching from Cuba up the American east coast to Canada. While hurricane-force winds battered the coastal southeast, tornadoes crisscrossed the south, and measurable snow fell as far south as the Florida panhandle. Record low temperatures (most of which stand today) were recorded all over areas east of the Mississippi River. All of these events took place over a three-day period: March 12-14, 1993. When they collided, all hell broke loose. A weak winter weather system moved southeastward from the Arctic over the Great Plains, as a hurricane-esque, thunderstorm-riddled band of low pressure rose out of the Caribbean, pushing northwest. When they collided, all hell broke loose.Here’s an example of the sheer extent of the storm: the highest wind gust, 144 mph, was recorded in Mt Washington, New Hampshire. The second highest was 109 mph in Key West, Florida. |

|

Military planes and helicopters Florida alone reported eleven tornadoes on March 12, while a storm surge of up to 11 feet creamed the Gulf Coast. The next day, six inches of snow fell in Orlando. Birmingham, Alabama reported 13”. Areas of Tennessee saw three or four feet of snow. The next day, sleet mixed with the snow that continued to fall in the mid-Atlantic states, adding dangerous ice to the mix. The strength and lasting power of the Superstorm was almost biblical—the whole system stalled overland. Nary an airport was left open. The only things in the air (aside from all the snow, obviously) were military planes and helicopters, which were in high demand along the water to rescue sailors stranded in violent, churning seas. Hundreds of hikers, too, had to be airlifted out of Appalachia. It’s difficult to camp in a 14-foot snowdrift.were in high demand along the water to rescue sailors stranded in violent, churning seas. Overall, nearly 10 million people lost power. 310 people were killed by snow, ice, water and wind. According to some NOAA estimates, 40% of the country was directly affected by freak weather. |

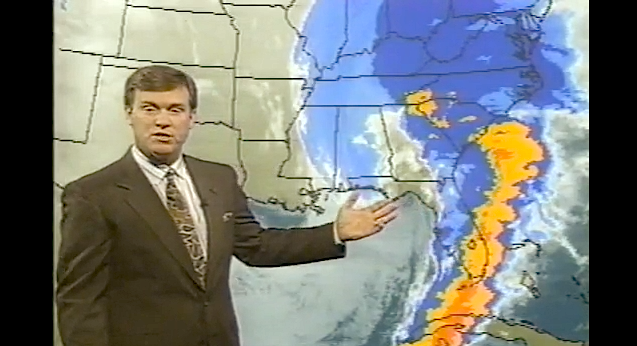

The curious thing about the 1993 Superstorm is that it was one of the first major weather events to be predicted with highly accurate forecast models. It also occurred at a time when most Americans owned VCRs. A quick search on YouTube reveals a wealth of weather-folk in front of large, green-dotted maps, gesturing to the massive comma-shaped storm. These old news clips, taped by home viewers, have been uploaded for anyone to view. Check out this Kentucky local news station’s Superstorm broadcast—the consumer run on video tapes is a nice touch: |

|

What compels someone to tape or upload brief clips of local news? I couldn’t say, but I’m certainly glad they did. Compare a 1993 weather broadcast to one today. Differences are evident not only in the weatherman’s hairpiece, but also in the data displays, the Doppler output, and the accuracy with which the anchors can predict precisely what will happen down to the hour. It’s only been eighteen years! *** 2003: The European Heat Wave I’m not a betting lady, but if I were to place a wager on the year that global warming exploded into the popular consciousness, I would easily choose 2003. Think about it: throughout the 1990s, the big environmental threats were things like the hole in the ozone layer, endangered pandas, genetically modified foods and landfill expansion. Now, I’m also not a scientist, so I don’t want to give you the impression that the blistering temperatures in Europe that year provably have a direct link to climate change. But by the time Al Gore’s climate crisis film An Inconvenient Truth came out in 2006, we knew what he was talking about. |

"Never during the Second World War did so many people die in one night in Paris, even during the bombings," says Dr. Patrick Pelloux in this 2003 BBC News special report. The months of July and August devastated Europe, but the general consensus is that it was the worst in France. Temperatures in Paris, typically in the mid-70s Fahrenheit that time of year, crossed into the triple digits. Department stores ran out of fans. People visited the catacombs in record numbers just to experience a few minutes in the cool, underground chambers. Meteo France, the national weather service, recommended a spritz of perfume in the air with the thought that, while you can’t do anything about the humidity and sweat, you can perhaps make it a little less unpleasant. |

|

Over 14,800 French citizens suffered heat-related deaths. Temperatures peaked at 108F in the south of France, where drought conditions added to the unbearable heat. All told, over 14,800 French citizens suffered heat-related deaths. It was only marginally better through the rest of Europe, with forest fires in Portugal, and extreme glacial melt through the Swiss Alps. Moldova lost 80% of its wheat crop. Even Cyprus, more accustomed to high temperatures, had to place a mandatory curfew on the entire country to prevent its citizens from being outside too much.Steel train tracks, built to withstand All told, 40,000 people died that summer. Forty thousand is an incomprehensible number of people. But the image that sticks in my mind from this event is of some train tracks—in Germany, if I recall correctly—that had completely warped in the intense temperatures. Steel train tracks, built to withstand the heat and pressure of high-speed rail activity, completely warped. It was like a Dali painting.the heat and pressure of high-speed rail activity, completely warped. |

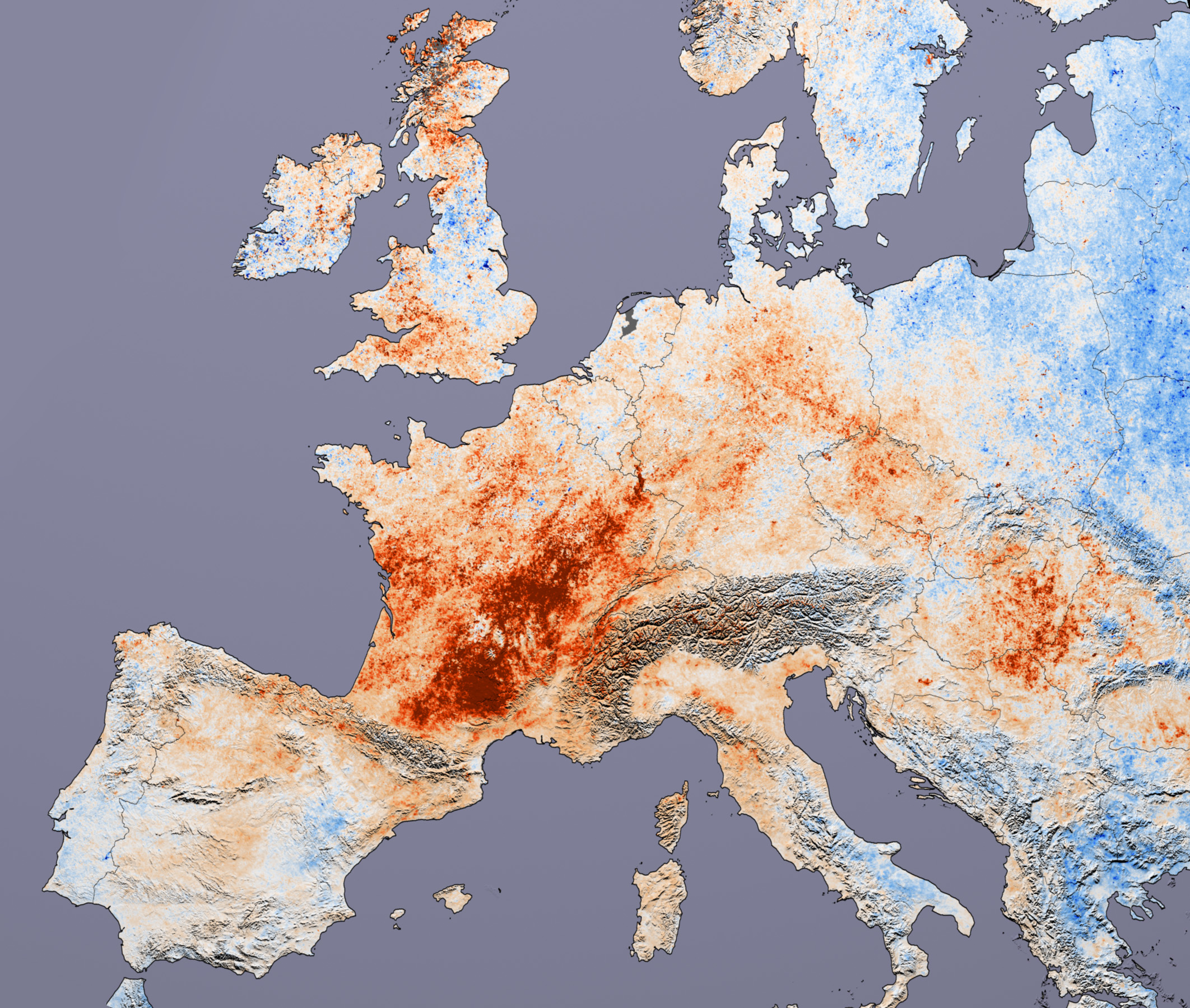

This map, created by NASA’s Earth Observatory, shows the land temperature discrepancy between seasonal average temperatures and 2003’s record-breaker, as observed by the MODIS. MODIS, or Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, measures surface temperature by spectral bands. It was launched in late 1999 as part of the Terra satellite, along with a group of other environmentally minded imagers. MODIS has sent back consistent and reliable data as well as stunning images of hurricanes, blizzards, and other natural phenomena. It can also track man-made events like the Deepwater Horizon oil slick in the Gulf of Mexico. Covering the entire earth every two days, Terra picks up a lot of information. |

|

Including the fact that the rest of the world that year experienced below-average temperatures. After the skies clear, the snow melts and the rain falls, not all disasters leave a mark as clear and lasting as Hurricane Katrina or Mt Pinatubo. But mapping catastrophes insures that precise geographic records are kept. Cartographers document the extent of the damage for future generations to have ready during the next call for mitigation. Everything—from evacuation routes, to insurance rates—takes a region’s history of disasters into account.  *** Victoria Johnson is a GIS (geographic information science) analyst and cartographer based in Washington, DC. She graduated from the Department of Geography of George Washington University. |