FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

EXERCISING CHOICE

EXERCISING CHOICE

PROZAC IS LUCRATIVE, BUT PROBLEMATIC.

DANIEL, NEUROPSYCHOLOGY STUDENT, PROPOSES

A CLASSICAL ANTIDEPRESSANT.

read the essay now >>

PROZAC IS LUCRATIVE, BUT PROBLEMATIC.

DANIEL, NEUROPSYCHOLOGY STUDENT, PROPOSES

A CLASSICAL ANTIDEPRESSANT.

read the essay now >>

|

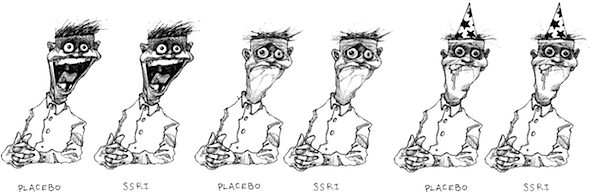

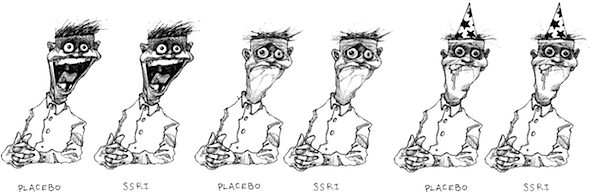

In the late 1980s, Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) were supposed to change the world. These drugs shifted the paradigm of psychiatric treatment for depression. The older generation of antidepressants, called MAOIs and Tricyclics, were known to be effective in the treatment of depression, but also carried a host of profound and life-altering side effects—making their use a very serious decision indeed on the part of the prescribing clinician. Unfortunately, they also carried a host of profound and life-altering side effects. By targeting only those neurotransmitter receptors likely involved in serotonin transmissions, SSRIs produced a much narrower range of side effects on the central nervous system than MAOIs and Tricyclics. The pharmaceutical marketing machine listened. Jubilant endorsement by the medical community—epitomized in books such as Listening to Prozac (1993)—was quick to follow the drug to the market. Safe and effective, SSRIs were supposed to dramatically lower the incidence of debilitating depression in our society.But depression remains a persistent condition that affects an apparently ever-growing proportion of the population. It may be true that SSRIs are likely as effective as older anti-depressants, but these |

drugs were prescribed sparingly, and only to the most hopelessly depressive cases. Tricyclics were rarely prescribed to patients suffering from mild to moderate depression. The apparent safety, and hence triviality, in prescribing SSRIs has led to an explosion in prescription writing. Between 1996 and 2002, prescription rates of anti-depressants increased by nearly 50%, after increasing more than 900% since 1984. By 2007, 118 million Americans (more than a third of the population) had been prescribed antidepressants. The majority of these were SSRIs (CDC, 2007). Antidepressants became the most frequently prescribed drugs in America. Following the jubilation of the years immediately following the release of Prozac, it was found that SSRIs are not especially effective in treating the vast majority of cases of depression. Furthermore, there is emerging evidence that SSRIs may not in fact be as safe as advertised. Serious potential side effects not seen in older anti-depressants—such as increased risk of suicide, and a life-threatening condition called serotonin syndrome—may be substantially under-reported (Kauffman, 2009). While the results of SSRI treatment for mild to moderate depression may be statistically significant, the effect size is miniscule (Fournier, DeRoubeis, Hollon, Dimidjian, Amsterdam, Shelton, and Fawcett, 2010). That is to say, that while patients who take SSRIs for mild to moderate |

|

depression see improvement in their condition at a higher rate than patients who do not take SSRIs, the extent of the improvement is negligible—and the patients still qualify as “depressed.” Clearly, SSRIs are not the final word in the treatment of depression. Serious potential side effects may be substantially under-reported. The Disney version of how SSRIs work can be found in any pamphlet you pick up from a doctor's office, or on a pharmaceutical company website. According to a 2004 televised Zoloft (the brand name of Sertraline, an SSRI manufactured by Pfizer) advertisement, depression is caused by an “imbalance” of a “natural chemical” called serotonin. What is known is that SSRIs do in fact change the way the brain deals with serotonin by increasing this neurotransmitter’s availability.The extent to which consumers are being misinformed cannot be understated. When serotonin passes from one neuron to the next, it crosses over a fluid-filled space called a synapse. The serotonin is then returned to the original cell via a process called “reuptake.” SSRIs, as their name would suggest, inhibit the reuptake |

of serotonin, causing it to remain in-synapse, and thus available to neural receptors for longer than is natural. While this mechanism has been demonstrated and verified, there has not in my opinion been a satisfactory inquiry into its ultimate function within the treatment of depression. In fact, the mechanism of SSRI action is extremely complex, in that it involves a host of serotonin receptor subtypes that do profoundly different things, depending on where they are in the brain. Serotonin very likely plays some role, but it is very clearly not the one indicated by the aforementioned pharmaceutical advertising (Carr and Lucki, 2011). The extent to which consumers are being misinformed on this topic cannot be understated. They are making money hand over fist by pumping out pills. As SSRIs (and a host of other treatments of questionable efficacy) rose, potentially more effective, yet less profitable techniques have garnered less enthusiasm. This is because biomedical research, as it is practiced in the United States, is a primarily commercial, rather than scientific endeavor. The incentives for pharmaceutical companies are simple: produce high-margin, low-cost treatments that can be prescribed in mass quantity. For pharmaceutical |

|

companies, the fact that SSRIs are not particularly effective, and may actually be less safe than alternatives, is of little real import: They are making money hand over fist by pumping out pills. For pharmaceutical companies, if not for depression patients, SSRIs are the magic bullet. There is another treatment for depression that has been demonstrated to be safe and effective. Researchers have been aware of its anti-depressant qualities since the mid-1980s (Martison, Medhus & Sandvik, 1985), as well as its potential outperformance of pharmacological therapies in terms of both significance and effect size. Conventional wisdom has pointed to it for as long as people have been getting sad. Its major side effects are weight loss, and improved cardiovascular health. This treatment is vigorous exercise. The research is not yet (though nothing ever is) conclusive, and researchers have noted a number of methodological problems in studies supporting the use of exercise in depression (Strohle, 2009). That being said, it is fair to say that there is reasonable body of evidence supporting the use of exercise as an effective treatment for depression, comparable in impact to that of chemical anti-depressants. |

So why are patients with depression referred to a pharmacist, and not a track coach? It is certainly not for lack of a viable way to explain how exercise could alleviate depression and anxiety. A growing body of evidence points to the possibility that certain psychopathologies, including depression, may be in part a function of reduced neuroplasticity (the production of new neural tissue and connections) in certain brain structures (Manji, Quiroz, Sporn, Payne, Denicoff, Gray, Zarate & Charney, 2003). Neuroplasticity in the hippocampus is associated with the learning of new behaviors, and the extinction of existing, problematic behaviors. The chemical Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) is a powerful tool in promoting neurogenesis. BDNF levels, along with those of other growth factors, are strongly correlated with exercise (Cotman and Berchtold, 2002). Along with several other neurotrophins, it is a likely key to the treatment of depression and anxiety. Exercise might well increase the availability of BDNF, in turn increasing the patient's ability to “unlearn” the maladaptive responses that lead to the production of depression symptoms. The meshing of biomedical research with the drive for profits is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the promise of profits can, and does spur significant investment in the continual research of treatments for a variety of medical conditions. |

On the other hand, it produces a number of what economists refer to as “perverse incentives”—which in this case refers to profit opportunities that are unquestionably contrary to the wider public interest, as well as to the progress of science. It is unfortunately not possible to obtain precise statistics on the amount of money being spent on SSRIs, as compared to exercise treatments for depression. I can confidently say, however, that there is far more money pouring into the continued research and promotion of SSRIs than ever will exist for non-prescription therapies. There are, nonetheless, a host of researchers that are aware of the problems associated with SSRIs and are on the hunt for alternatives. As I graduate and embark on a career in neuroscience, I aim to join these efforts in earnest.  |

WORKS CITED Carr, G., and Lucki, I. (2011). The role of serotonin receptor subtypes in treating depression: a review of animal studies. Psychopharmacology. 213 (2), 265-287. Kramer, P. (1993). Listening to Prozac. Penguin Books. London, England. Manji, H., Quiroz, J., Sporn, J., Payne, J., Denicoff, K., Gray, N., Zarate, C., & Charney, D. (2003). Enhancing neuronal plasticity and cellular resilience to develop novel, improved therapeutics for Difficult-to-Treat depression. Biological Psychiatry. 53(8), 707-742. Strohle, A. (2009). Physical activity, exercise, depression and anxiety disorders. Journal of Neural Transmission. 116(6), 777-784. Martinsen, E., Medhus, A., & Sandvik, L. (1985). Effects of aerobic exercise on depression: a controlled study. British Medical Journal. 291, 109. Kauffman, J. (2009). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) drugs: More risks than benefits? Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons. 14(1), 7-12. Fournier, J., DeRubeis, R., Hollon, S., Dimidjian, S., Amsterdam, J., Shelton, R., & Fawcett, J. (2010). Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity. 306(17), 1829-1940. . |