FORTNIGHT ISA MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTARY PROJECT ON THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION: THE LAST GENERATION TO REMEMBER A TIME WITHOUT THE INTERNET. |

HIJACKING MYTH #4

HIJACKING MYTH #4

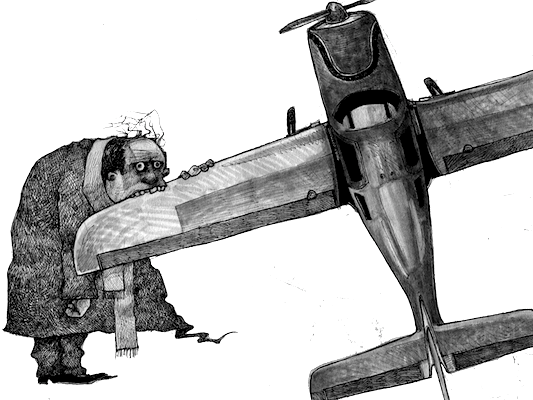

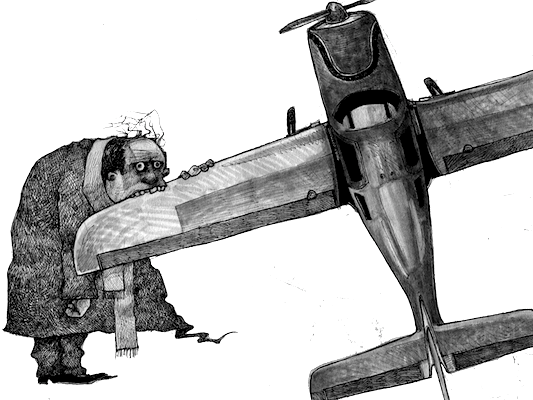

WHEN MAN EATS METAL,

THE PLANE HIJACKS HIM.

DOLAN OFFERS A FOURTH MYTHOLOGY.

Read the essay now >>

WHEN MAN EATS METAL,

THE PLANE HIJACKS HIM.

DOLAN OFFERS A FOURTH MYTHOLOGY.

Read the essay now >>

|

If, as someone once put it, “myth is a way of speaking,”1 then Michel Lotito, by reversing the process, may have invented something entirely new. Besides winning the Tour de France multiple times, he is famous for eating “bicycles, shopping carts, a metal coffin, a cash register, a washing machine, a television, and 660 feet of fine chain.”2 Unspeakably, this man, who calls himself Mr. Mangetout—French for eat everything—draws these items into his mouth in a fantastic display of impossible narrative. Sign and signified are digested in wholly new scenarios, inverting the iconography and objectification of standard mythos. For the first time in history, the airplane Each object he eats is a kind of story, told backwards by Lotito, piece by fabulous piece, the plot borne silently into his body—“but the Frenchman’s crowning achievement is eating his way through an entire four-seater Cessna light aircraft. That’s roughly 2,500 pounds of aluminum garnished with steel, vinyl, Plexiglass, rubber and sundry nuts and bolts.”3 In an absurd subversion, for the first time in history, the airplane has hijacked a person.has hijacked a person. |

If the airplane has invaded Lotito’s body, as in the case of a hijacker boarding a jetliner, then the first question we must ask ourselves is: where does the airplane want to go? To pose an answer to this question, we must investigate the life and culture of the airplane; that routine from which it wishes to escape via stolen human bodies. Typically, the aircraft is filled by others and it enjoys unbroken movement, and—as in the case of a squid—“the world apprehended by him is a fluid and liquid world which precipitates into” its body, where “his purpose in knowing the world is to digest it.”4 By hijacking a person, it is clear what an airplane wants: it desires, instead of carrying others to their destinations, to have itself brought outward by others in “a gesture that advances against the world.”5 Moreover, it wants to know our limits, our two dimensional space, where “our world is a plane, a tundra.”6 Simply, it wants to be taken into our restrictions, those things which it has never known before. Like Lotito swallowing in order to speak, the aircraft wants to be contained in order to expand, the constraint becoming its cathartic release. Lotito must pass all this metal at some point, and by escaping a world of unbounded volume into one of deeply restricted density, the aircraft desires—desperately—to need morning coffee, to wait impatiently at a bus stop and to tire pointlessly |

|

away at some undeserving work, to be flushed down the drain of routine. In defiance of its limitless freedom, it wants to know the entrapment of human mobility, the active hammering against social norms and expectations that people—those braggarts perpetually teasing an airplane’s freedom—so flagrantly enjoy. In defiance of its limitless freedom, it wants to know the entrapment of human mobility. It is worth considering, as well, what Lotito gets out of this arrangement. “The Man Who Eats Everything” approaches the task of the airplane casually, consuming it in foot-long chunks over two years. We are reminded of Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar, a collage of the Lepidoptera life stages. Like the caterpillar too, Lotito is changing: his doctor says that “Lotito cannot eat soft objects such as bananas or hard-boiled eggs. His body is so accustomed to passing difficult solid objects that he cramps up with something soft in his stomach.”7 So, like the reader of the children’s book, we must ask ourselves: why is he eating so much? and, more importantly, what will he become? The fact that the “Cessna 150 is a Very Easy Plane to Steal”8 is an important clue. That Lotito would allow himself to be hijacked by an aircraft—one itself so readily stolen—speaks to a heightened kind of |

submission. His is a surrender not to any airplane, but to the meekest among them. The image comes to mind of a calm and enlightened man, at peace with the objects and world around him. With deep meditations such as Lotito’s “One begins to think that all does not lie within one’s own fire, but that something exists outside, that an outside exists somewhere over there.”9 Is this what he’s after, transcendance? And if that is his goal—then he seeks what the Vedic texts call soma, “the substance that was free from death, and that freed from death.”10 This possibility is not unlikely, considering that one must “snatch soma from the sky” from a “footless creature.”11 What lives in the sky and doesn’t have feet? What lives in the sky and doesn't have feet? The airplane. “It is as if the soma, the substance that is the essence of all substance, that fills mind and veins, that is the ultimate guardian of the world’s existence, could only be obtained thanks to some crime, some act of violence: an excess of giving or taking.”12 Lotito, certainly, has exemplified an excess of taking. He embodies the idea that “Everything down here is devouring or devoured”13 and is about to become something else. Yet we must remember that the airplane is already a kind of transcendence, and to consume one is to become not just any new being, |

|

but something exponential —the collage of paper and glue that represents metamorphosis itself. *** Dolan Morgan is a writer whose fiction and poetry can be found in venues such as Armchair/Shotgun and The Believer (upcoming). For previous pieces in Dolan's series on the mythology of hijacking, see: Myth One; Myth Two; Myth Three. The next column provides a list of the author's reference notes, citing historical periodical research. |

REFERENCE NOTES 1. Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. 2-3. Mestel, Rosie. “Open Wide: Amazing Eaters Can Down Almost Anything.” The Spokesman Review. March 13, 1992. 4-6. Fluser, Vilem. Novaez, Rodrigo Maltez. Ed., Tr. Vampyroteuthis Infernalis. New York: Atropos Press. 1987. 7. O’Donnell, Carey. “‘M. Monge-tout Plans to Eat a Plane.” The Montreal Gazette. November 16, 1978. 8. Mathews, Mark; Fairhall, John; Denniston, Lyle. “Cessna 150 is a Very Easy Plane to Steal.” The Baltimore Sun. September 13, 1994. 9-13. Calasso, Roberto. Parks, Tim., Tr. Ka: Stories of the Mind and Gods of India. Vintage Books: New York. 1998. |