On the first day of the capstone class of my university’s geography major, Senior Seminar in Geographic Thought, our professor brought up a name none of us had heard before: David Helgren. Our professor circled the class, handing out unlabeled maps of the United States and the world.

“This.” He paused, drumming his fingertips on the podium.

We shifted in our seats, looking at each other sideways. We 27 constituted the largest graduating class the geography department had seen in a decade.

“This is a pop quiz.” Fifty-four eyes rolled. “David Helgren was a geography professor at the University of Miami, he lost his job as a result of this quiz. I would like to keep my job, so please give this the old college try, hmm?”

On the US side, we labeled Washington DC, Miami, Cleveland, a handful of other significant cities. On the world side, Iraq, Afghanistan, Sudan, Colombia—countries we read about in the news every day. As we dutifully labeled our maps, he described what happened with David Helgren: Helgren gave the quiz to his UM students and, as he expected, they bombed. What he didn’t expect was the extent of the, uh, bombage. Half of the class couldn’t locate Chicago. Most missed London.

Everyone loves a good “kids these days!” story, and the angle on this one was that American university students—particularly ones from the University of Miami—were a bunch of know-nothings. A group of UM law students sued for loss of future income with the argument that Helgren’s results had marred the worth of their degrees. Helgren was summarily dismissed from his position at the university.*

That was 1983, two years before I was born. The situation has not improved. There have been a bunch of studies since Helgren’s initial quiz and the results are never positive. They’re also an amazing source for scare stats: a 1989 Gallup poll by the National Geographic Society’s then-president Gilbert M. Grosvenor challenged young people (ages 18-24) in nine countries to label sixteen locations on a world map. Americans averaged 7/16, and only 25% could label the Persian Gulf, despite the US teetering on the brink of the Gulf War.**

A 2002 National Geographic survey—an expanded version of the 1989 poll—asked 56 questions to assorted young people (same age range, same countries). Scored by traditional letter grades, Sweden got a B, the best results, with an average score of 40. Germany and Italy averaged 38. The US? 23. That’s a D. Ouch. They did it again in 2006, and found that only 37% could label Iraq on a map. Fifty-four percent could not, when given the country of Sudan, identify the continent to which it belonged.

There are twelve areas of “core education” mentioned in former President Bush’s divisive 2002 No Child Left Behind plan. Geography is, believe it or not, one of them. There is, however, one significant difference: Economics, arts, and American history are all federally funded.

Of all the subjects of study addressed by NCLB, geography alone was appropriated precisely zero dollars. It was also the only subject without a structured plan for educational improvement. Though this is just one of the many glaring deficiencies in NCLB, why bother including geography as an area of core education but provide teachers will no funding, resources, or structure? Paying geography empty lip service won’t show the other 63% where Iraq is on the map.

Increasingly rolled in with history and social studies education, geography gets buried under memorizing names and dates for state and national standardized tests. A quick, informal survey of my group of friends**** reveals that many of us cite the PBS television program Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? as their main source of geography education. Despite my entering Kindergarten in 1990, the pull-down maps throughout middle school at my school district (one of the top public districts in the state at the time), still included the USSR.

It’s not just the US. Geography education is lacking around the world. Only 26% of Japanese students could locate Iraq on a map, according to a survey by the Association of Japanese Geographers. Seven percent couldn’t find Tokyo. Down under, after a report was published noting the decline in Australians studying geography at a higher level, the Australian Minister of Education found geography classroom time to be insufficient. Educators often bundled its study with "current affairs." This is not a bad way to learn. As Mark Twain once said, “God created war so that Americans would learn geography.” But this approach is strikingly limited, and does not stick.

Geography gets only slightly more respect at the university level. None of the Ivy League schools have a geography department - Harvard, once the center of American geographic thought, extinguished their geography department in 1948—and, as I mentioned above, the largest graduating class of geographers at my university***** included fewer than 30 people. My freshman year saw the department move into a posh new building that, up until then, had been housed in a converted pharmacy.

Still, the National Center for Education Statistics reports that the number of geography degrees awarded has been on a steady rise since the late 1980s. Similarly, the discipline’s largest professional body, the Association of American Geographers, today boasts the largest membership in the organization’s 107-year history at just over 10,000 members. Lots of young folks are entering the field and it’s a great time to be a geographer. The introduction of accessible GPS and especially Google Earth has led to an explosion in the general person’s interest in geography, which in turn leads to more jobs for GIS analysts, cartographers, geographers, and any number of positions for geography professionals. It’s not quite recession-proof (what is?), but as far as today’s job market goes, geographic know-how is in demand. Also borne of the general person’s increased interest in geography? So many map rounds at pub quiz nights.

There is a federal effort underway as well. The Teaching Geography is Fundamental act, introduced this year as HR 885 and Senate Bill 434, vows to provide grants for efforts to improve American geographic literacy. Heavily lobbied for by (you guessed it!) the National Geographic Society as well as the American Association of Geographers, TGIF would have appropriated $15,000,000 for geography education. The bill was co-sponsored by Rep. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD), Rep. Thomas Petri and Rep. Tim Walz (D-MN) in the House and Senators Thad Cochran (R-MS) and Barbara Mikulski (D-MD). Though it's not exactly likely to become law any time soon, the fact that TGIF enjoys bipartisan support is a step in the right direction. It has actually been introduced before, in 2005. Each time around, the bill gains more supporters. More than 20 Senators and 120 Representatives from both parties signed on as co-sponsors. Who knows; maybe one day it’ll even make it out of committee!

As for that quiz we geography majors took in the beginning of class? We all passed. Granted, we were nearing the close of four years of intense geographic studies, most of us having elected to take a course called “Regions of the World” where we combed through every part of the world’s political and physical geographies.******

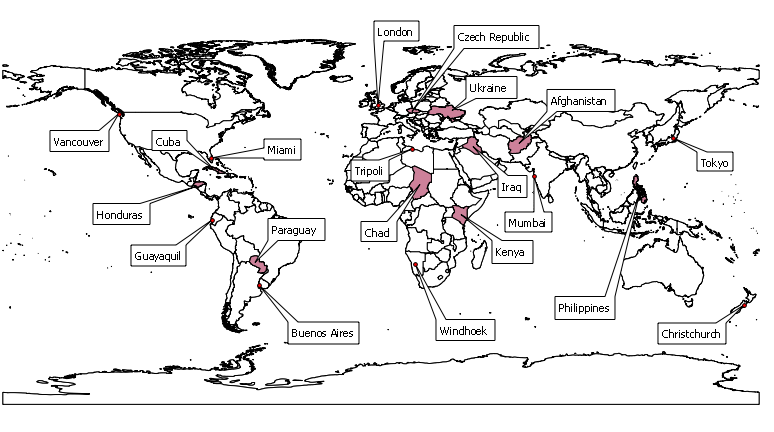

Do you think you could pass the quiz? Do you want to find out? The next page contains a modified version, a map of the world and a list of 20 locations. The following slide has the answers. See how you stack up!

*There is a thorough retelling of Helgren’s quiz and the aftermath in Ken Jennings’ book Maphead.

** the abysmal results of this poll sparked the creation of the National Geographic Bee

*** There is no second law on the books, but Waldo Tobler is still alive and I suppose he might produce a second. Anyway: yes, the only law of geography says “thing” four times in one sentence. I like that, it’s an easy way to convey that the discipline is all-encompassing. You can apply Tobler’s Law to almost anything. Here, the other day I mapped out barbecue sauce types. Of course the ketchup-using style is located between the vinegar-using style and the tomato-using style! Tobler’s Law! I would show you the map, but it was drawn on a napkin. With sauce.

****I asked about 25 people at a party, 18 mentioned WitWiCS?. Not exactly Gallup over here, but it’s something.

*****The George Washington University. Regardless of what you hear about GW stereotypes, they have an excellent, if diminutive, geography department.

******Read a little about Astana, Kazhakstan sometime and tell me you aren’t dying to check out that architecture.

“This.” He paused, drumming his fingertips on the podium.

We shifted in our seats, looking at each other sideways. We 27 constituted the largest graduating class the geography department had seen in a decade.

“This is a pop quiz.” Fifty-four eyes rolled. “David Helgren was a geography professor at the University of Miami, he lost his job as a result of this quiz. I would like to keep my job, so please give this the old college try, hmm?”

On the US side, we labeled Washington DC, Miami, Cleveland, a handful of other significant cities. On the world side, Iraq, Afghanistan, Sudan, Colombia—countries we read about in the news every day. As we dutifully labeled our maps, he described what happened with David Helgren: Helgren gave the quiz to his UM students and, as he expected, they bombed. What he didn’t expect was the extent of the, uh, bombage. Half of the class couldn’t locate Chicago. Most missed London.

Half of the class couldn't locate Chicago.

Most missed London.

One in ten couldn’t locate Miami. Helgren passed the results onto his colleagues. A few weeks later, an article appeared in the campus newspaper. National newspapers picked up on the story, and soon Helgren was the center of a media firestorm.Most missed London.

Everyone loves a good “kids these days!” story, and the angle on this one was that American university students—particularly ones from the University of Miami—were a bunch of know-nothings. A group of UM law students sued for loss of future income with the argument that Helgren’s results had marred the worth of their degrees. Helgren was summarily dismissed from his position at the university.*

That was 1983, two years before I was born. The situation has not improved. There have been a bunch of studies since Helgren’s initial quiz and the results are never positive. They’re also an amazing source for scare stats: a 1989 Gallup poll by the National Geographic Society’s then-president Gilbert M. Grosvenor challenged young people (ages 18-24) in nine countries to label sixteen locations on a world map. Americans averaged 7/16, and only 25% could label the Persian Gulf, despite the US teetering on the brink of the Gulf War.**

A 2002 National Geographic survey—an expanded version of the 1989 poll—asked 56 questions to assorted young people (same age range, same countries). Scored by traditional letter grades, Sweden got a B, the best results, with an average score of 40. Germany and Italy averaged 38. The US? 23. That’s a D. Ouch. They did it again in 2006, and found that only 37% could label Iraq on a map. Fifty-four percent could not, when given the country of Sudan, identify the continent to which it belonged.

Geography education, of course, is so much more than just labeling places on a map.

Geography education, of course, is so much more than just labeling places on a map. But it’s a fine indicator of an individual’s geographic awareness. After all, you need to know where things are to fully understand their relationship with one another. The field of geography has one law, Tobler’s First Law, which states that "Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things.”*** A basic understanding of geographic principles relies on having some knowledge of relative location. Without that, you’re nowhere. You are actually no where.There are twelve areas of “core education” mentioned in former President Bush’s divisive 2002 No Child Left Behind plan. Geography is, believe it or not, one of them. There is, however, one significant difference: Economics, arts, and American history are all federally funded.

Of all the subjects of study addressed by NCLB, geography alone was appropriated precisely zero dollars. It was also the only subject without a structured plan for educational improvement. Though this is just one of the many glaring deficiencies in NCLB, why bother including geography as an area of core education but provide teachers will no funding, resources, or structure? Paying geography empty lip service won’t show the other 63% where Iraq is on the map.

Increasingly rolled in with history and social studies education, geography gets buried under memorizing names and dates for state and national standardized tests. A quick, informal survey of my group of friends**** reveals that many of us cite the PBS television program Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? as their main source of geography education. Despite my entering Kindergarten in 1990, the pull-down maps throughout middle school at my school district (one of the top public districts in the state at the time), still included the USSR.

It’s not just the US. Geography education is lacking around the world. Only 26% of Japanese students could locate Iraq on a map, according to a survey by the Association of Japanese Geographers. Seven percent couldn’t find Tokyo. Down under, after a report was published noting the decline in Australians studying geography at a higher level, the Australian Minister of Education found geography classroom time to be insufficient. Educators often bundled its study with "current affairs." This is not a bad way to learn. As Mark Twain once said, “God created war so that Americans would learn geography.” But this approach is strikingly limited, and does not stick.

This year, President Obama released a plan to amend No Child Left Behind.

His plan did not mention geography.

I don’t mean to blame teachers or public school for these failings. Teachers are under increasingly arduous strain to teach larger class sizes new and difficult information in order to pass a series of year-end exams, often with their jobs at stake. Many teachers pay for their own school supplies out of pocket. Still, the problem must be remedied, and it won’t happen without serious effort from the national level as well as with individual school administrators. This year, President Obama released a plan to amend No Child Left Behind. His plan did not mention geography.His plan did not mention geography.

Geography gets only slightly more respect at the university level. None of the Ivy League schools have a geography department - Harvard, once the center of American geographic thought, extinguished their geography department in 1948—and, as I mentioned above, the largest graduating class of geographers at my university***** included fewer than 30 people. My freshman year saw the department move into a posh new building that, up until then, had been housed in a converted pharmacy.

Still, the National Center for Education Statistics reports that the number of geography degrees awarded has been on a steady rise since the late 1980s. Similarly, the discipline’s largest professional body, the Association of American Geographers, today boasts the largest membership in the organization’s 107-year history at just over 10,000 members. Lots of young folks are entering the field and it’s a great time to be a geographer. The introduction of accessible GPS and especially Google Earth has led to an explosion in the general person’s interest in geography, which in turn leads to more jobs for GIS analysts, cartographers, geographers, and any number of positions for geography professionals. It’s not quite recession-proof (what is?), but as far as today’s job market goes, geographic know-how is in demand. Also borne of the general person’s increased interest in geography? So many map rounds at pub quiz nights.

There is a federal effort underway as well. The Teaching Geography is Fundamental act, introduced this year as HR 885 and Senate Bill 434, vows to provide grants for efforts to improve American geographic literacy. Heavily lobbied for by (you guessed it!) the National Geographic Society as well as the American Association of Geographers, TGIF would have appropriated $15,000,000 for geography education. The bill was co-sponsored by Rep. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD), Rep. Thomas Petri and Rep. Tim Walz (D-MN) in the House and Senators Thad Cochran (R-MS) and Barbara Mikulski (D-MD). Though it's not exactly likely to become law any time soon, the fact that TGIF enjoys bipartisan support is a step in the right direction. It has actually been introduced before, in 2005. Each time around, the bill gains more supporters. More than 20 Senators and 120 Representatives from both parties signed on as co-sponsors. Who knows; maybe one day it’ll even make it out of committee!

As for that quiz we geography majors took in the beginning of class? We all passed. Granted, we were nearing the close of four years of intense geographic studies, most of us having elected to take a course called “Regions of the World” where we combed through every part of the world’s political and physical geographies.******

Do you think you could pass the quiz? Do you want to find out? The next page contains a modified version, a map of the world and a list of 20 locations. The following slide has the answers. See how you stack up!

***

*There is a thorough retelling of Helgren’s quiz and the aftermath in Ken Jennings’ book Maphead.

** the abysmal results of this poll sparked the creation of the National Geographic Bee

*** There is no second law on the books, but Waldo Tobler is still alive and I suppose he might produce a second. Anyway: yes, the only law of geography says “thing” four times in one sentence. I like that, it’s an easy way to convey that the discipline is all-encompassing. You can apply Tobler’s Law to almost anything. Here, the other day I mapped out barbecue sauce types. Of course the ketchup-using style is located between the vinegar-using style and the tomato-using style! Tobler’s Law! I would show you the map, but it was drawn on a napkin. With sauce.

****I asked about 25 people at a party, 18 mentioned WitWiCS?. Not exactly Gallup over here, but it’s something.

*****The George Washington University. Regardless of what you hear about GW stereotypes, they have an excellent, if diminutive, geography department.

******Read a little about Astana, Kazhakstan sometime and tell me you aren’t dying to check out that architecture.