Genomic instability is a hallmark of many cancers. Understanding the mechanisms that ensure genomic stability is an important and worthwhile research pursuit, because it will allow us to understand what belies many pathological conditions at the genomic level. Eventually, this study could lead to preventative or therapeutic treatments.

The forbearer of genomic instability and its relation to cancer biology was the published account Zur Frage der Entstehung maligner Tumoren, or; “Concerning the Question of the Origin of Malignant Tumors,” written by German biologist Theodor Boveri in 1914. Extrapolated from chromosome studies that used developing sea urchins, Boveri argues with prescience that tumor malignancy occurs as a consequence of chromosomal abnormalities. He further predicts the existence of tumor suppressors.

Typically, cytogenetic techniques are employed to study the manifestation and effects of genomic instability. The field of cytogenetics studies the structure and function of the chromosomal content of the cell.

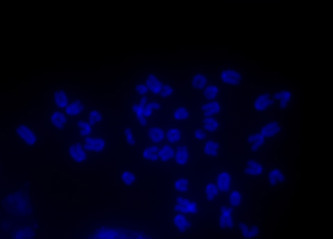

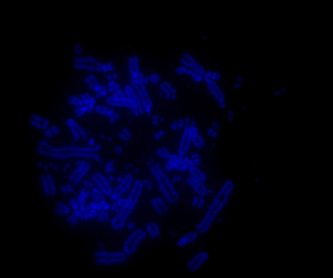

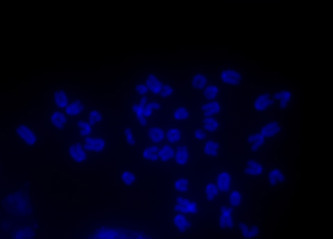

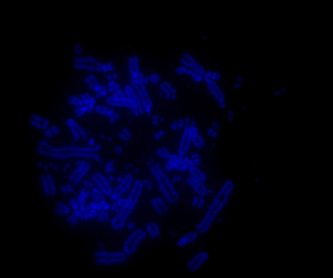

One basic cytogenetic technique is karotype analysis (see images 1 and 2 for examples), where the number and appearance of individual chromosomes within chromosome spreads are scored for abnormalities. Another technique that I use is called fluorescent in-situ hybridization (see images 3 and 4 for examples), or FISH, which employs fluorescent probes to detect and label the spatial location of specific DNA segments on chromosomes, or within interphase nuclei.

Rather than explain my work in a text format, I would like the images I gather to speak for me.

Images 1, 2: DAPI karyotype metaphase cells

Image 1 shows a DAPI. DAPI is a blue dye that stains DNA, so in these images, the chromosomes are stained blue. Karyotype metaphase chromosome spread from an untreated cell. This karyotype is normally observed for the cells used.

Image 2 shows a DAPI karyotype from a treated cell. Compared to the control (Image 1), this is a highly aberrant karyotype: there are numerous chromosomal fragments and breaks present. It is astonishing to believe that this cell was alive before processing.

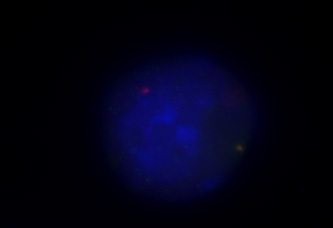

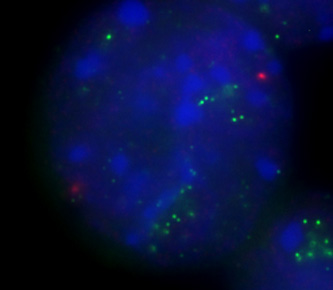

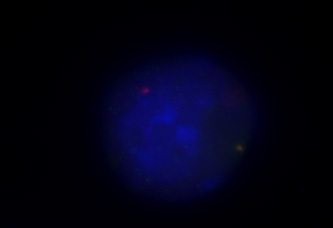

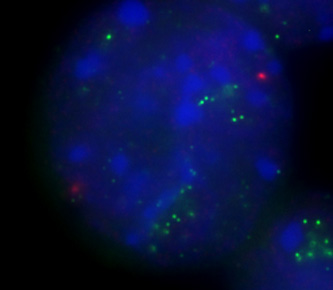

Images 3, 4: Three-Channel Interphase Cells

Images 3 and 4 show multi-channel snapshots of untreated interphase cells. The blue stain is again DAPI, a DNA stain that denotes the nucleus of the cells. The red foci indicate a fluorescent probe that binds to specific genomic loci (again, the experimental technique to label this is called fluorescent in-situ hybridization, or FISH). The green foci indicate a fluorescent-labeled protein that signifies DNA double-strand breaks.

In the untreated cell (Image 3), there is only one DNA break that coincides with the gene of interest (merged yellow foci). In the treated cell, there are numerous DNA breaks located outside of the gene of interest.

The field of cytogenetics studies the structure and function of the chromosomal content of the cell.

The forbearer of genomic instability and its relation to cancer biology was the published account Zur Frage der Entstehung maligner Tumoren, or; “Concerning the Question of the Origin of Malignant Tumors,” written by German biologist Theodor Boveri in 1914. Extrapolated from chromosome studies that used developing sea urchins, Boveri argues with prescience that tumor malignancy occurs as a consequence of chromosomal abnormalities. He further predicts the existence of tumor suppressors.

Typically, cytogenetic techniques are employed to study the manifestation and effects of genomic instability. The field of cytogenetics studies the structure and function of the chromosomal content of the cell.

One basic cytogenetic technique is karotype analysis (see images 1 and 2 for examples), where the number and appearance of individual chromosomes within chromosome spreads are scored for abnormalities. Another technique that I use is called fluorescent in-situ hybridization (see images 3 and 4 for examples), or FISH, which employs fluorescent probes to detect and label the spatial location of specific DNA segments on chromosomes, or within interphase nuclei.

Rather than explain my work in a text format, I would like the images I gather to speak for me.

Images 1, 2: DAPI karyotype metaphase cells

Image 1 shows a DAPI. DAPI is a blue dye that stains DNA, so in these images, the chromosomes are stained blue. Karyotype metaphase chromosome spread from an untreated cell. This karyotype is normally observed for the cells used.

Image 2 shows a DAPI karyotype from a treated cell. Compared to the control (Image 1), this is a highly aberrant karyotype: there are numerous chromosomal fragments and breaks present. It is astonishing to believe that this cell was alive before processing.

Images 3, 4: Three-Channel Interphase Cells

Images 3 and 4 show multi-channel snapshots of untreated interphase cells. The blue stain is again DAPI, a DNA stain that denotes the nucleus of the cells. The red foci indicate a fluorescent probe that binds to specific genomic loci (again, the experimental technique to label this is called fluorescent in-situ hybridization, or FISH). The green foci indicate a fluorescent-labeled protein that signifies DNA double-strand breaks.

In the untreated cell (Image 3), there is only one DNA break that coincides with the gene of interest (merged yellow foci). In the treated cell, there are numerous DNA breaks located outside of the gene of interest.